This op-ed first appeared in Florida Politics

Last week, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed House Bill 7125 into law. Unfortunately, this long-discussed criminal justice reform legislation falls short of committing to meaningful change.

In passing this bill over more comprehensive proposals, Florida legislators threw away real criminal justice reform and millions of taxpayer money.

When the Florida Legislature convened its 2019 Session in March, the state was plagued by the overuse of mass incarceration and a corrections budget that had ballooned to $2.4 billion.

The Session ended May 4 with just as many people in prison — but now the corrections budget is $2.7 billion.

Many Florida families had pinned their hopes on promises of criminal justice reform. Extremely minor fixes were made around the edges of the profoundly flawed criminal justice industry in Florida. But the principle problem remains: Florida continues to throw away lives and massive amounts of money in ways that do nothing to keep our communities safer.

This is personal for me; I have a son in prison. But my family is only one of thousands suffering from a system that continues to believe in costly punishment rather than smart rehabilitation.

At one crucial juncture in the Session, legislators could have saved Florida taxpayers more than $800 million over the next five years. Currently, all persons convicted of felonies in Florida must serve 85 percent of their sentences. A bill passed by the Senate this year would have allowed nonviolent offenders who had exhibited good behavior and taken advantage of educational opportunities to be released after completing 65 percent of their sentences. Experts estimated that as many as 9,000 people could have gone free in the next several years — saving $20,000 per year per inmate.

But that reform was eventually rejected.

Another proposed cost-saving measure would have taken two reforms that were passed by legislators in recent years, reducing the mandatory sentences for certain crimes — including possession of small amounts of some opioids — and would have made them retroactive. In other words, lawmakers decided certain sentences were too extreme and unfair, but only for those convicted in the future, not those already behind bars. That makes absolutely no sense when it comes to either justice or economics.

In yet another failure, the legislature did not address, in any serious way, the processing of kids in adult courts. Florida sentences more youth to adult prisons than any other state and more than California, Texas, New York and Pennsylvania combined.

The legislature responded by eliminating the mandatory processing of certain juveniles as adults. And, while that change has the potential to impact up to a third of the cases that are affected, many of those minors will almost certainly end up in adult courts anyway after prosecutors make their decisions.

The current law still leaves the decision on “direct file” to the adult system in the hands of prosecutors, not judges. Neither children processed in adult courts nor their families have any way to appeal the decisions of those prosecutors.

In 1986, Florida set the threshold at which a theft became a felony — not a misdemeanor — at $300. This year, after more than three decades of inflation, lawmakers finally raised that amount, but only to $750. Meanwhile, in Georgia and Alabama the amount is $1500 and in Texas, $2500. So, while it is no longer a felony to steal an iPhone 6S, it still is for an iPhone 8.

Florida has another serious problem in the frequency with which it suspends driver’s licenses. In 2017, 280,000 people lost licenses for offenses that had nothing to do with driving. This year, lawmakers removed some misdemeanors from that list of offenses — petty theft, supplying tobacco or alcohol to a minor — but it was a drop in the bucket. Working people are seriously affected when their licenses are suspended. Yet another instance when lawmakers were oblivious to the effects on taxpayers’ wallets.

Along the way, lawmakers failed to address a critical problem that exists throughout Florida’s population whether adult or juvenile: racial bias and the disproportionate percentage of people of color funneled into the criminal justice system. Black people make up 17 percent of Florida’s population, but 47 percent of prison inmates are Black.

The Senate bill, adopted on a bipartisan basis, would have required that any criminal justice bill carry with it an assessment of the racial impact of that new law. It would have cost next to nothing to implement, but it was squashed.

Other Southern states have made much more progress on criminal justice issues, largely because they could no longer bear the cost of mass incarceration. Our lawmakers, meanwhile, have created a reputation for Florida as the most recalcitrant of the former Confederate states, unwilling to shed its Jim Crow past and willing to waste money to boot.

Only a collective group of fools would be professionally and ethically comfortable sustaining a stagnant system of mass incarceration.

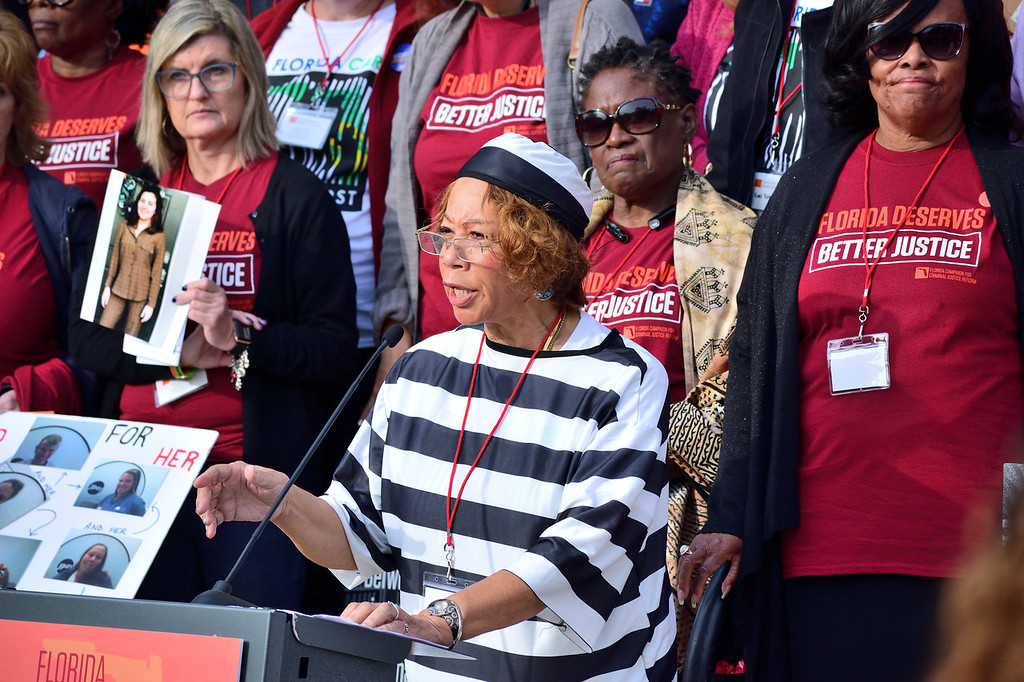

Judy Thompson is the director of the Forgotten Majority, a nonprofit that advocates for prisoner’s rights.

Date

Tuesday, July 9, 2019 - 2:00pmFeatured image