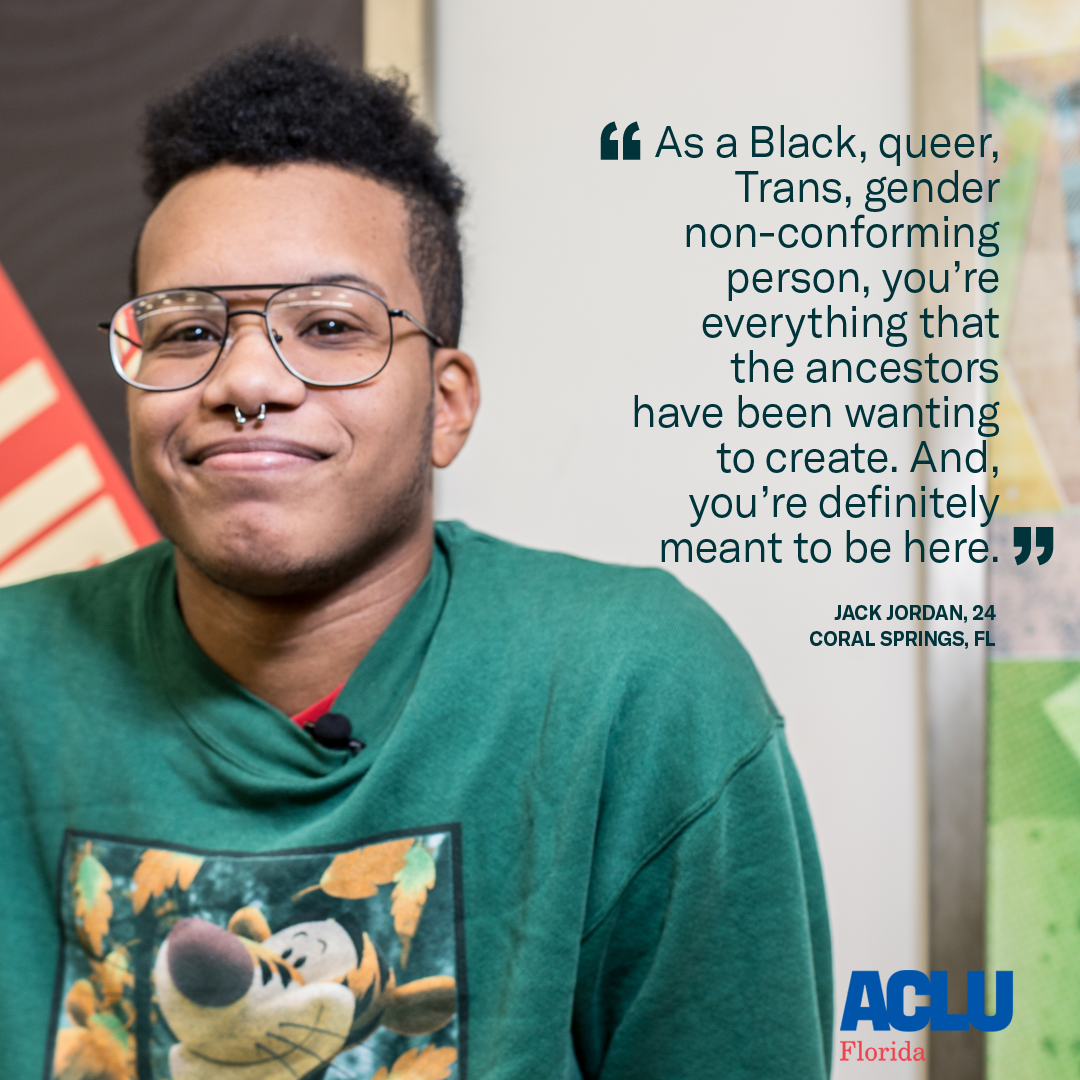

This feature is part of the ACLU of Florida's "LGBTQ+ Youth Activist Project" commemorating Pride Month during the month of June.

"My name is Jack. I'm 24-years-old and I live in Coral Springs, Florida."

Q: How does your work make our community a more inclusive and open place for everyone, regardless of where they come from, how they identify, or who they love?

A: "Right now, I work at AIDS Healthcare Foundation as a Transgender Cultural Sensitivity Intern.

"I feel like people need to know that the trans community is not a monolith, but rather something very diverse and very nuanced."

Q: What do you see as the most pressing issue currently affecting LGBTQ youth? What do you think will help alleviate it?

A: "The trans community as a whole does not have access to healthcare or competent healthcare. They don't have access to equal opportunities, and it just becomes more difficult with more nuances that comes with this person's identity or who they are as a person.

"I believe that when it comes to equal access or equal opportunity, when it comes to healthcare, trans people have to really decide whether it's even worth going to a doctor or to get tested or to get the care that they need because they struggle with the thought of even going through a traumatic, discriminatory experience. Or, going and maybe getting actual care that's not focused solely on their trans identity.

"The South Florida community thinks about the current administration's constant pullback on the rights of everybody, but also the trans community. The repeal of abortion rights affects everybody, not just women. It affects trans men who might be pregnant. It affects trans people that may be struggling with pregnancy or who want to get an abortion. It's not solely a women's issue.

"Stonewall Rising Legavcy is an organization I'm building that focuses on the empowerment and the social justice development of queer youth in South Florida. We give them the tools to feel empowered in themselves and to know that they can cause active change in their own communities, when they go back home maybe to a house that doesn't accept them.

"We're very much focused on making sure that they feel seen and making sure that they feel like they have a chance to not just survive but thrive, instead of just trying to exist in a world that they feel is not made for them. It's very much and we have to make them realize that the power is inside of them."

Q: What message of encouragement would you like to send to LGBTQ youth who may not have the love and support to know that they are worthy and capable of being themselves, regardless of circumstance?

A: "Being Black, and being queer, and being trans is very hard. But, there are more of us out there and there's people ready to love on you for who you are, specifically when it comes to your Blackness, your queer-ness, your trans-ness.

"As a Black, queer, trans, gender-nonconforming person, you're everything that the ancestors have been wanting to create."

Jack Johnson, 24, from Coral Springs, Florida.

Date

Friday, June 21, 2019 - 5:45pmFeatured image