In a move that would make even Senator McCarthy blush, the Trump administration is threatening to pull federal funding from a Middle East Studies program for failing to toe the government’s line on Islam and Muslims.

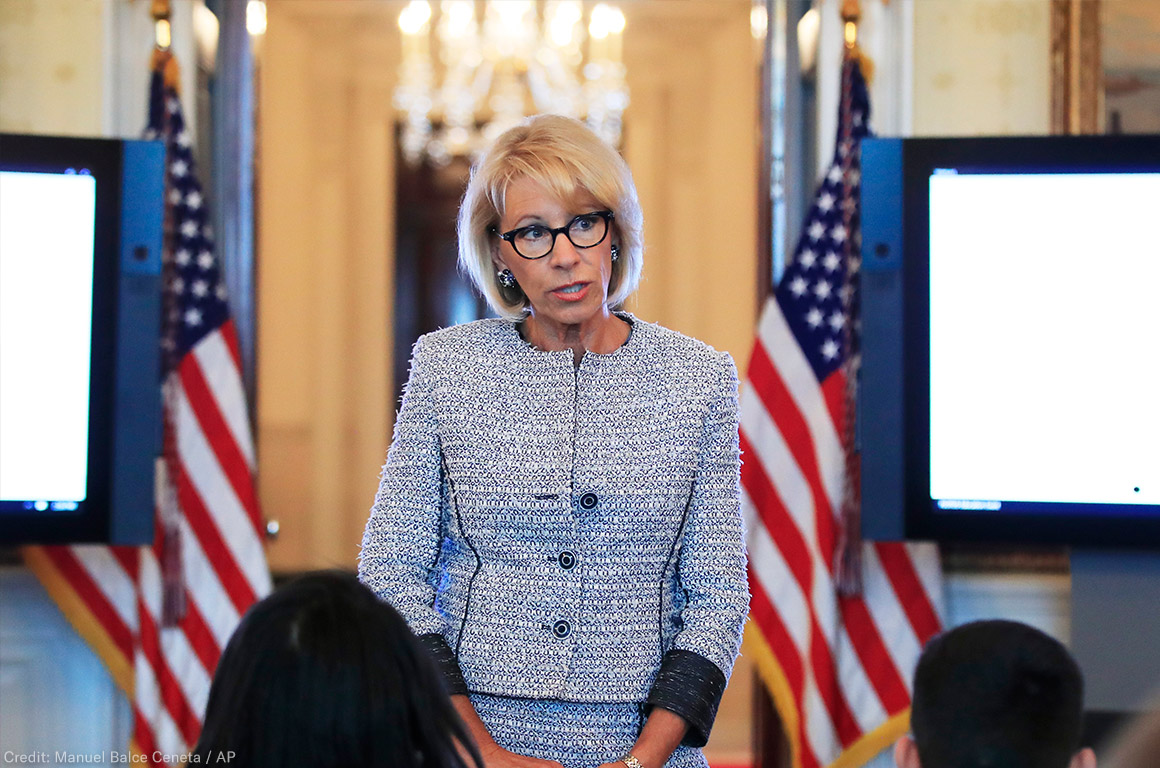

Last week, Betsy DeVos’s Department of Education sent a letter to administrators of the Duke-UNC Consortium for Middle East Studies — a jointly run program that receives federal funding under Title VI of the Higher Education Act — warning that the department would cut the Consortium’s federal aid unless the Consortium submits plans to remake its Middle East studies program and curriculum to the department’s satisfaction. Among other complaints, the department demanded that the Consortium temper its portrayal of “the positive aspects” of Islam and cease “advancing ideological priorities.”

The department’s attempt to inject the Trump administration’s long pattern of anti-Muslim bigotry and discrimination into higher education represents a significant threat to academic freedom at colleges and universities like UNC and Duke. In response, the ACLU sent a letter today urging Secretary DeVos to end the department’s investigation into the Consortium and to prevent future attempts to politicize federal funding for higher education. We also filed a Freedom of Information Act request for records related to the department’s decision to investigate the Consortium as well as any similar investigations the department may have undertaken at other educational institutions that receive Title VI funding.

The origins of the Education Department’s investigation are as troubling as the letter itself. In June, Secretary DeVos ordered an inquiry into whether the Duke-UNC Consortium misused its Title VI funds to sponsor a conference on the Gaza conflict, after a member of Congress accused the conference of “radical anti-Israel bias.” As it turned out, less than $200 of federal funds were spent on the event. When this allegation didn’t stick, it appears that the department — not content to let the matter rest — scoured the Consortium’s programming to ferret out other objectionable viewpoints and purported deficiencies.

The department identifies a number of ways in which the Consortium supposedly violates the Title VI funding requirements, not only complaining about the curriculum’s inclusion of “positive aspects of Islam” but also accusing the Consortium of inappropriately “advancing ideological priorities.” As we explain in our letter to Secretary DeVos, however, it is the Department of Education — not the Consortium — that inappropriately attempts to advance ideological priorities

Although the government may attach certain conditions to the use of federal funding — such as compliance with statutory and constitutional requirements — the proud boast of our universities is that they are free from the ideological micromanagement of the government censor. Title VI does not, and cannot, authorize the government to require federal funding recipients to de-emphasize the “positive aspects of Islam” to the Department’s satisfaction. The Department’s assumption of such authority threatens core constitutional principles protecting freedom of speech and freedom of religion.

This ham-fisted attempt to wield funding authority over the Consortium’s academic programming illustrates yet again the Trump Administration’s deep-seated anti-Muslim bias. It should also be alarming to anyone who cares about academic freedom, a bedrock principle of higher education.

Higher education institutions throughout the country are now on false notice that federal funding requires conformity to the Trump administration’s ideological standards. The Department’s ultimatum issued to the Consortium will no doubt have a chilling effect on these institutions as they determine the curricular content of federally funded programming. That’s why we’re asking Secretary DeVos to terminate the Department’s investigation into the Duke-UNC Consortium and to take affirmative measures to prevent similar politicized investigations in the future.

Colleges and universities are under no obligation to further the administration’s anti-Muslim agenda. The government has a constitutional obligation to respect that.

Nicola Morrow, Paralegal, ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project

& Heather L. Weaver, Senior Staff Attorney, ACLU Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief

Date

Friday, September 27, 2019 - 11:15amFeatured image