Sex workers aren’t always a part of the conversation about police brutality, but they should be. Police regularly target, harass, and assault sex workers or people they think are sex workers, such as trans women of color. The police usually get away with the abuse because sex workers fear being arrested if they report. If we lived in a world that didn’t criminalize sex work, sex workers could better protect themselves and seek justice when they are harmed.

Protecting sex workers from police violence is just one of the reasons we need to decriminalize sex work. It would also help sex workers access health care, lower the risk of violence from clients, reduce mass incarceration, and advance equality in the LGBTQ community, especially for trans women of color, who are often profiled and harassed whether or not we are actually sex workers. In 2020 the call for decriminalization has made progress, but there are still widespread misconceptions about sex work and sex workers that are holding us back. Some even think that decriminalization would harm sex workers. That isn’t true.

Here are five reasons to decriminalize sex work that would protect sex workers, help hold police accountable, and ensure equality for all members of society, including those who choose to make a living based by self-governing their own bodies.

Decriminalization would reduce police violence against sex workers

Police abuse against sex workers is common, but police rarely face consequences for it. That’s partly because sex workers fear being arrested if they come forward to report abuse. Police also take advantage of criminalization by extorting sex workers or coercing them into sexual acts, threatening arrest if they don’t comply. Criminalizing sex work only helps police abuse their power, and get away with it.

If sex work were decriminalized, sex workers would no longer fear arrest if they seek justice, and police would lose their power to use that fear in order to abuse people.

Decriminalization would make sex workers less vulnerable to violence from clients

Like the police, sex workers’ clients can also take advantage of a criminalized environment where sex workers have to risk their own safety to avoid arrest. Clients know they can rob, assault, or even murder a sex worker — and get away with it — because the sex worker does not have access to the same protections from the law.

Sex workers became even more vulnerable to abuse from clients after the passage of SESTA/FOSTA in 2018. The ACLU opposed this law for violating sex workers’ rights and restricting freedom of speech on the internet. SESTA/FOSTA banned many online platforms for sex workers, including client screening services like Redbook, which allowed sex workers to share information about abusive and dangerous customers and build communities to protect themselves. The law also pushed more sex workers offline and into the streets, where they have to work in isolated areas to avoid arrest, and deal with clients without background checks.

Decriminalization would allow sex workers to protect their own health

Sex workers sometimes go without medical care out of fear of arrest or poor treatment by medical staff if it comes out that they are a sex worker. And because the law doesn’t treat sex work like a real job, sex workers do not have access to employer-based health insurance, which means that many cannot afford care.

Criminal law enforcement of sex work comes with unjust police practices, like the use of condoms as evidence of intent to do sex work. As a result, some sex workers and people who are profiled as sex workers may opt not to carry condoms due to the risk of arrest. This puts them at risk of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

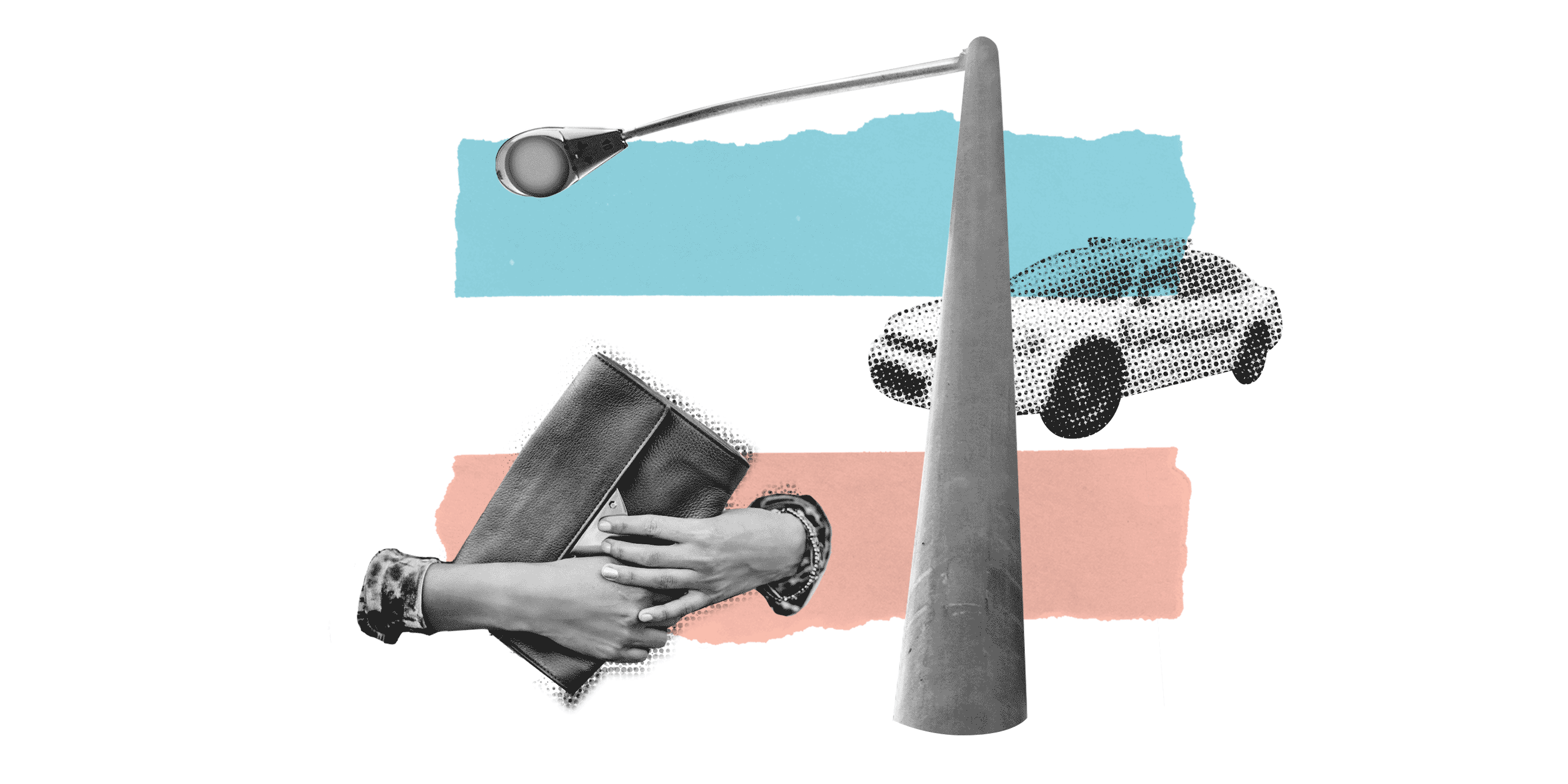

Decriminalization would advance equality for the LGBTQ community

Sex work criminalization laws impact the whole LGBTQ community because members of the community — particularly LGBTQ people of color, LGBTQ immigrants, and transgender people — are more likely to be sex workers. The passage of anti-sex work laws like SESTA/FOSTA harms the community by dramatically decreasing incomes, which further marginalizes members of the trans community, people of color, or those with low incomes to begin with.

Trans women of color feel the impact of criminalization the most, whether or not we are sex workers. Police profile us and often press prostitution charges based on clothing or condoms found in a purse. We can’t go about our lives without fear of being targeted by police.

If sex work is decriminalized, police would have one less tool to harass and marginalize trans women of color. Sex workers, and especially trans women, would be more able to govern their own bodies and livelihoods. Decriminalizing sex work would promote the message that Black trans lives matter.

Decriminalization would reduce mass incarceration and racial disparities in the criminal justice system

The criminalization of sex work feeds the mass incarceration system by putting more people in jail unnecessarily. Those incarcerated tend to be trans and/or people of color, two groups that are already disproportionately incarcerated. One in six trans people have been incarcerated, and one in two trans people of color.

Incarceration is violent and destructive for everyone, and even more so for trans people. While incarcerated, trans people are often aggressively misgendered, denied health care, punished for expressing their gender identity, and targeted for sexual violence.

An arrest on charges of sex work can result in life-changing consequences that last long past the end of a sentence. A criminal record can prevent you from accessing an accurate ID, jobs, housing, health care, and other services. It can also lead to deportation for immigrants. Members of the trans community and sex workers already face discrimination in many of these systems. A criminal record further marginalizes and stigmatizes being trans or engaging in sex work.

Decriminalizing sex work would be a major step toward decarceration and reducing racial disparities in the criminal justice system. It would keep sex workers from being harmed by the collateral consequences of a criminal record. It would help prevent the marginalization of sex workers and destigmatize sex work.

How to decriminalize sex work

The ACLU has supported decriminalizing sex work since 1973, and it became an official board policy in 1975. Since then, affiliates across the country have advocated for decriminalization at the state level by striking down laws restricting sex workers’ rights, such as condoms-as-evidence laws.

The fight continues in 2020, with active decriminalization bills in several state legislatures and advocates pushing elected officials like district attorneys to take pledges to not prosecute sex work. At the federal level, Congress has introduced the SAFE SEX Worker Act, which would study the effects of SESTA/FOSTA. There is a chance for progress if we educate each other on sex workers’ rights and pressure elected officials to decriminalize.

Sex workers deserve the same legal protections as any other people. They should be able to maintain their livelihood without fear of violence or arrest, and with access to health care to protect themselves. We can bring sex workers out of the dangerous margins and into the light where people are protected — not targeted — by the law.

LaLa B Holston-Zannell, Trans Justice Campaign Manager, ACLU

Date

Wednesday, June 10, 2020 - 1:00pmFeatured image