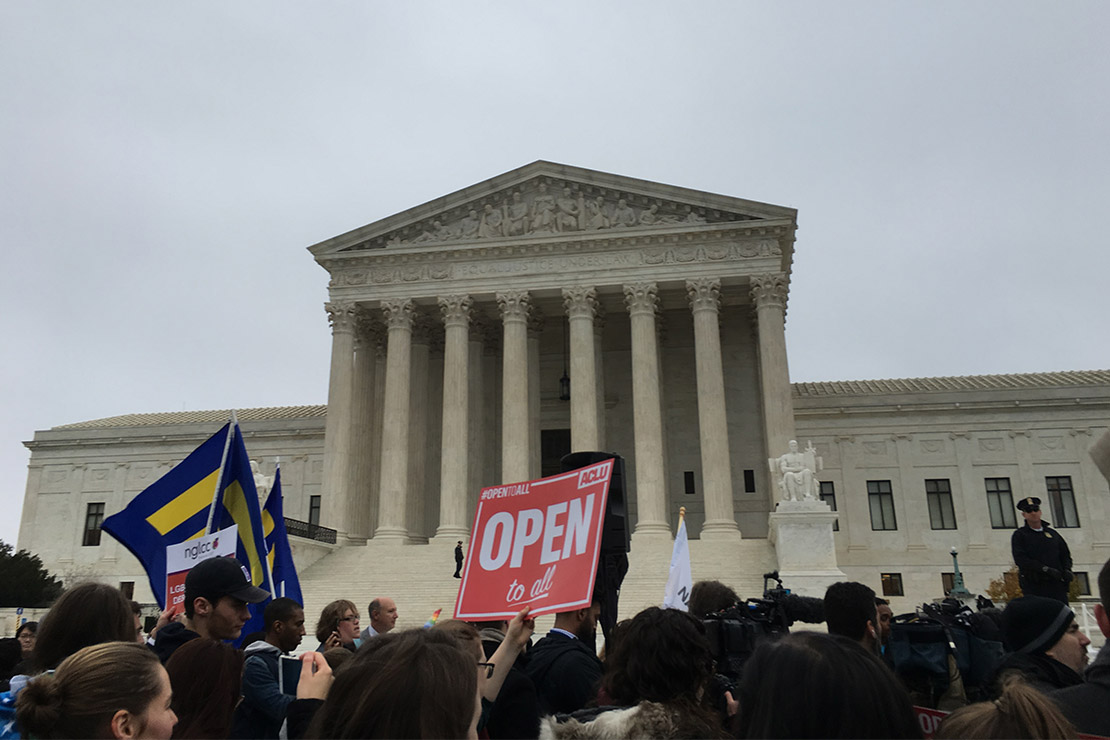

On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 6-3 decision that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the federal ban on sex discrimination in employment, protects LGBTQ workers from discrimination. The decision was based on a straightforward reading of the law: Discriminating against someone because they are LGBTQ is inherently sex discrimination. In his dissent, Justice Alito raised concerns about implications for employers with religious objections to hiring LGBTQ people, but the questions before the court in Monday’s monumental victory for LGBTQ workers did not involve whether the employers had a religious right to fire LGBTQ people. The court made clear that the scope of any religion-based defenses offered by Title VII, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, and the constitutional protections for religious exercise would be addressed in future cases.

The court will have a chance to weigh in on these questions sooner than you might think, since the next big LGBTQ rights case is already on the docket for the fall.

In Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, Catholic Social Services (CSS) is challenging a Philadelphia requirement that agencies contracting with the city to provide government services must not discriminate. The ACLU represents the Support Center for Child Advocates and Philadelphia Family Pride, and we are supporting the city’s right to require all of its contracted foster care agencies to accept all qualified families and put the best interests of children first.

CSS receives public money to provide foster care services, a core government service, and argues that because of its religious beliefs, it has the right to discriminate against same-sex couples interested in becoming foster families. CSS says both that the city’s policy singles it out for unfair treatment — even though CSS requires all foster care agencies to follow the same policy — and that the Supreme Court should make it easier for anyone with any kind of religious objection to refuse to follow any law, including our laws against discrimination. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against CSS, and the Supreme Court granted review in February.

Fulton isn’t the only case where these arguments are coming up, it just happens to be the one the court has already agreed to hear. In another case, Minton v. Dignity Health, a Catholic hospital system is asking the Supreme Court to reverse a lower court ruling that rejected the health care chain’s claim that religious objections give it a right to deny gender-affirming healthcare to transgender people, in violation of California law. And in the long-pending case of Ingersoll and Freed v. Arlene’s Flowers, a business is once again asking the Supreme Court to rule that because the owner of the business has religious objections to marriages of same-sex couples, Washington State’s nondiscrimination law is unenforceable against the business with respect to its refusal to sell a same-sex couple flowers for their wedding.

If the question in the workplace discrimination cases brought by Aimee Stephens, Donald Zarda, and Gerald Bostock was what the law means, the question in these next cases is when and whether the law matters. Don’t get me wrong: It is a tremendous victory for the court to say that the plain words of the law protect LGBTQ people, just like everyone else. But that victory is fragile and will be eroded if the court furthers the agenda of the Trump administration by giving anyone who objects on religious grounds a free pass to violate the law.

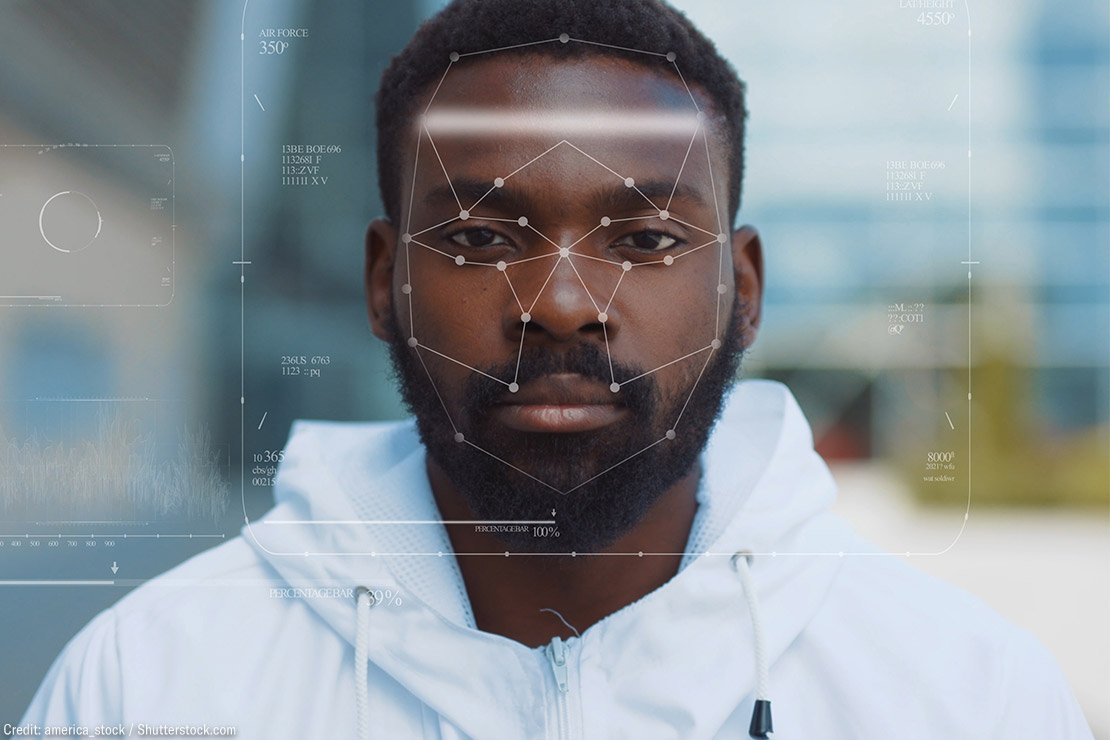

Decades ago, the fight for our civil rights laws was led by Black people who demanded legal protections from rampant discrimination. Those bedrock civil rights laws have been under attack since their passage, including by demands for religious exceptions. The latest attacks on civil rights protections in the Fulton case and the others that follow it won’t just compromise the Bostock decision and LGBTQ rights. Members of minority faiths, women, and people of color are all at risk, and those who live at the intersection of multiple identities are even more vulnerable. These next cases are about whether laws intended to allow full participation in public life will continue to apply to us all, or if those who object can use their religious beliefs to humiliate, exclude, reject, and deny access and care. While we know well that legal protections don’t automatically translate into full equality, they are an important step, and a rule saying that anyone who wishes to discriminate can do so would gut those hard-fought laws.

Since it already has the Fulton case before it, we hope the court will take this opportunity to declare that there is no constitutional license to discriminate.

Rose Saxe, Deputy Director, LGBT & HIV Project, ACLU

https://www.aclu.org/news/lgbt-rights/scotus-must-now-ensure-lgbtq-people-are-not-turned-away-from-taxpayer-funded-programs