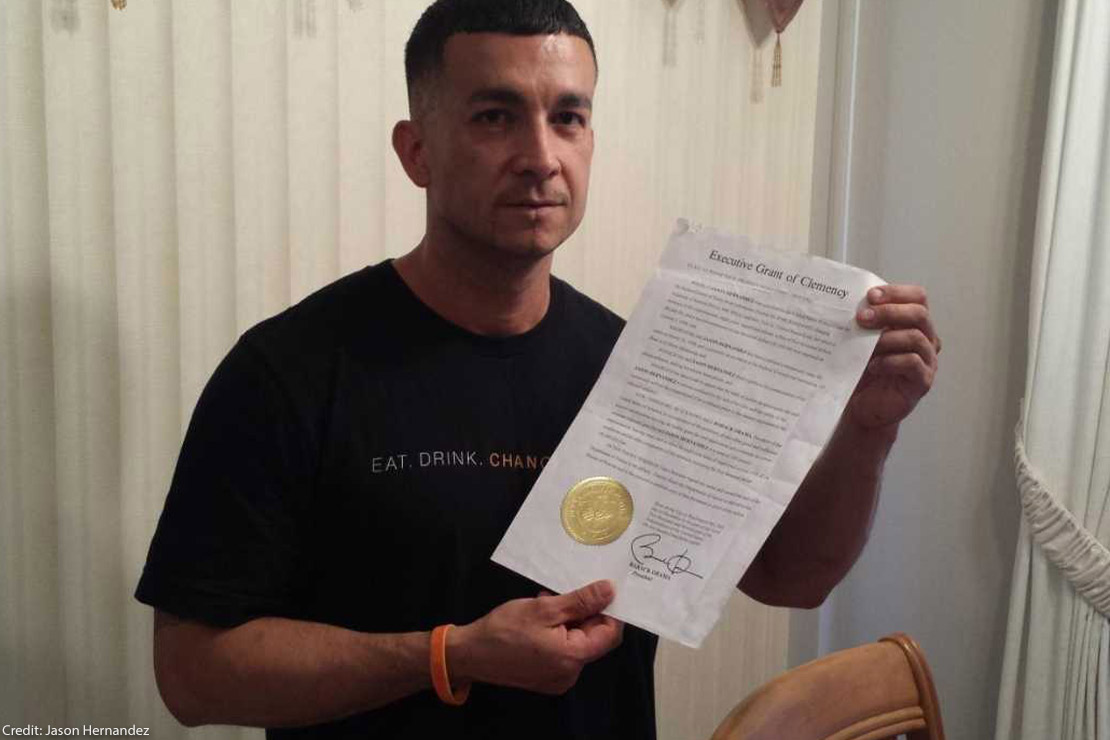

In 1998, at the age of 21, I was sentenced to life without parole plus 320 years for drug-related offenses that were committed mostly in my teens. In 1998, 16 years into my sentence, I received clemency from President Obama after writing a letter to him asking for forgiveness, asking for mercy, asking for understanding that I wasn’t a bad kid, just a kid who made a bad decision. That I wasn’t that person who roamed those streets long ago or the same person who stood in front of the judge and received a life sentence, and as a result I shouldn’t die in prison.

President Obama agreed.

I was extremely fortunate. Those who sought a commutation of their sentence before Obama’s presidency, when George W. Bush was in office, had a 1 in 1,000 chance of success. While conducting research as I prepared my own clemency application, I learned that only one other person serving life without parole for a drug offense had ever been granted clemency. Because of this, I have always compared my clemency to hitting the lottery. But instead of winning millions of dollars, I won my freedom.

Unfortunately, I am just one of the thousands upon thousands of people who after years or even decades in prison, have matured and changed their way of thinking. But because of mandatory minimums and truth in sentencing laws(another supposedly “tough on crime” sentencing scheme that is really just tough on people), and the inaccessibility or unreliability of parole, there are no judicial remedies to acknowledge the transformations of these individuals.

However, there is an extraordinary executive power that allows a show of mercy to be made: clemency.

Clemency has historically been relied upon in America as an olive branch extended to those unduly harmed by our system of mass punishment. It has been used as a tool to heal people, communities, and our very nation, and in doing so, has engendered reconciliation among its citizens. Clemency is a corrective measure that counteracts some of the effects of a flawed system. But the degree to which it can do so is mirrored by the degree to which it is used. Though it may often be overlooked today, clemency has been a key facet of our republic since its founding.

Alexander Hamilton, who played a pivotal role in ratifying the Constitution, saw the value of investing in the office of the presidency the ability to grant clemency to groups during periods of national crisis. Hamilton outlined this in the Federalist Papers: “In seasons of insurrection or rebellion, there are often critical moments, when a well-timed offer of pardon to the insurgents or rebels may restore the tranquility of the commonwealth; and which, if suffered to pass unimproved, it may never be possible afterwards to recall.”

Not long after this statement, President George Washington would use his pardon power after the suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794. The President pardoned two people who were considered leaders of the rebellion and had been sentenced to death. Washington’s legacy was later echoed in President Lincoln’s choice to issue 64 pardons for war-related offenses. They were part of his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, his blueprint for the reintegration of the South into Union.

In the century that followed, between 1918 and 1920, more than 2,000 people were convicted of sedition and other violations of the Espionage Act for speaking out against the American involvement in World War I. In 1921, President Warren Harding reacted by issuing blanket pardons to all those convicted under the Espionage Act. Still decades later, attempting to bring a close to the era of American conflict in Vietnam, President Jimmy Carter offered a blanket pardon to any American who had dodged the draft during the war.

These are all examples of how Presidents exercised their clemency power during and after periods of war to bring the nation together so that it might move forward in unity. That legacy must be resurrected again today to combat the legacy of another war: the war on drugs and related “tough on crime” policies that have actually been a war on Black and Brown communities.

These pervasive modern wars have left about 80 million people in this country with arrest records, 8 million with felony convictions, and more than 2 million people currently in our jails and prisons. With statistics like these, and decades of harsh crime policies in place, we can debate which policies should have been implemented and which shouldn’t have. But one thing is clear: America’s “tough on crime” movement was misguided, ill-advised, and has hurt the communities it intended to help.

From former President George Bush to current President Donald Trump, and from Govs. Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania to Kevin Stitt of Oklahoma, elected officials have exercised their clemency power to give individuals back their freedom, many of whom have been in prison for years or decades under “tough on crime” laws enacted in the 1980s.

I was one of those fortunate souls, and my release granted me more than freedom. It was a chance at redemption.

Clemency is not and should not be viewed as a tool used by officials who are “soft on crime.” Instead, it is a tool whose use signals an official’s wisdom about our nation and the nature of our mass punishment system, whose roots lie in slavery but whose functions are present in the lives of too many people today. These punishments that may have appeared necessary and just at one time, but their lie has been exposed: Putting too many people in prison for too long does not keep people safe, and it certainly does harm to the loved ones of those who are incarcerated.

In a 2003 speech, former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy referred to pardon power as a necessity to ensure justice is administered and adjusted over time:

“A people confident in its laws and institutions should not be ashamed of mercy. The greatest of poets remind us that mercy is ‘mightiest in the mightiest. It becomes the throned monarch better than his crown.’ I hope more lawyers say to chief executives, ‘Mr. President,’ or ‘Your Excellency, the Governor, this young man has not served his full sentence, but he has served long enough. Give him what only you can give him. Give him another chance. Give him a priceless gift. Give him Liberty.’”

I know personally that when the gift of clemency is given to a person, it reverberates throughout our souls that we are not only a nation of opportunity, but also of second chances, of mercy and hope — even for those who may have done wrong — even for those in prison. For as Justice Kennedy said in his closing remarks on clemency, “[S]till, the prisoner is a person. Still he or she is part of the family of humankind.”

Date

Wednesday, August 5, 2020 - 10:30amFeatured image