More than 20 years ago, 23-year-old Amadou Diallo was gunned down in front of his apartment in the Bronx by the NYPD. Diallo had been walking home when four officers mistook him for a suspect in a rape investigation, firing a total of 41 shots at him and hitting him 19 times after mistaking his wallet for a gun. All four officers were later acquitted of charges related to his death.

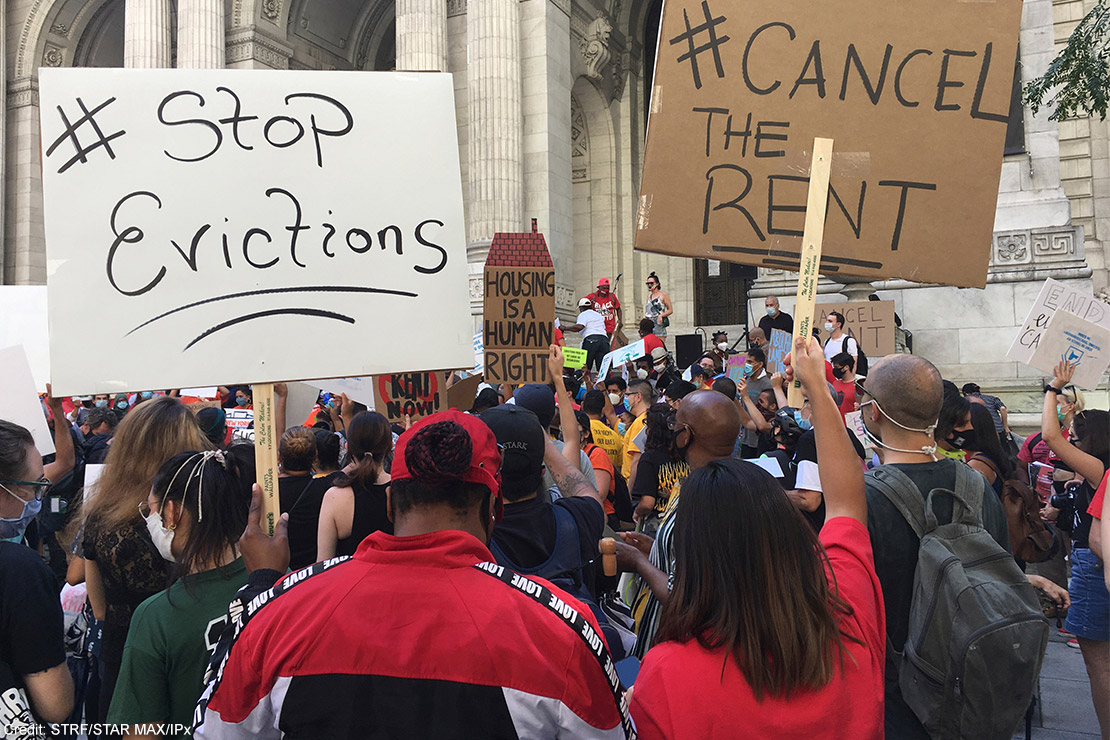

Diallo’s death sparked a massive protest movement in New York City, with echoes of this summer’s demonstrations over the murder of George Floyd. Furious calls for police reform were dismissed by then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, who called the protests “silly.” In retrospect, the killing is a signpost in America’s long history of police violence against Black people, and a tragic symbol of how little has changed.

What’s often lost in the memory of Diallo’s death, though, is the way it also highlighted the dangers that Black immigrants encounter in America. Diallo was of Guinean origin, arriving in New York just a little over a year before his death. He didn’t share much by way of background or life experiences with his Black American neighbors, but what he did share was the color of their skin.

Because of that, whether he knew it or not when he first arrived here, Diallo was living with the same risk of police violence that they were. For Black immigrants, life in the U.S. often means being encircled by the same systems of criminalization, profiling, and over-policing as Black Americans.

His death was an extreme example of that risk, but a police encounter doesn’t need to generate big headlines to have life-altering and even deadly outcomes for immigrants. Because of harsh laws that mandate severe penalties for non-citizens who come into contact with the criminal justice system, an arrest that might typically lead only to probation or a few weeks in jail can trigger months or years spent in immigration detention and eventually, deportation to a country they may barely know.

These laws, combined with ever-present aggressive policing in the majority-Black neighborhoods where they live, create an additional layer of punishment for Black immigrants in a legal system already skewed against them. During a summer where millions have poured onto the streets to yell “Black Lives Matter,” advocates from Black immigrant communities say that should include theirs as well.

“Irish and Italian immigrants, along with some white-passing Latinx immigrants, can assimilate into white America,” said Abraham Paulos, director of policy and communications for the Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI). “Black immigrants don’t have that option. We’re integrated into Black America along with all the systems of oppression and discrimination.””

The number of Black immigrants in America has grown steadily since the 1980s. Now, around one in 10 Black people in America were born overseas. But despite their numbers, they rarely feature prominently in immigration discourse. This means the specific issues they face often go overlooked.

Despite only making up around 7 percent of the non-citizen population, Black immigrants represent over 20 percent of those in deportation proceedings on criminal grounds. Local jails and police often act as feeders for ICE, and where local ordinances bar that type of cooperation, ICE agents have been known to scour court dockets in order to make arrests inside courthouses.

The list of crimes that can trigger deportation is vast, and includes minor offenses such as drug possession, turnstile jumping, DUI, and writing a bad check. And for immigrants who get caught in the criminal justice system, automatic detention in an ICE facility often follows a sentence or arrest.

Once they wind up in one of those facilities, it’s nearly impossible for immigrants to be released while they fight their case in court. This can mean months or years in detention facilities that are notorious for atrocious conditions and abuse. Black immigrants fare particularly poorly in those facilities – one recent study found that they were placed into solitary confinement six times more often than other immigrants. In Louisiana, a group of detained Cameroonians have now been on a hunger strike related to conditions in the Pine Prairie ICE detention center for more than three weeks.

And while ICE doesn’t track racial demographic data of the people it deports, in the first year of the Trump administration deportations to countries in sub-Saharan Africa rose almost across the board.

https://twitter.com/joepenney/statuses/1274107763350745089

Paulos says that while the criminal justice and immigration enforcement systems are technically separate, from the perspective of many Black immigrants, it’s hard to tell them apart.

“It’s really just an attachment on the pipeline,” he said. “There’s the school-to-prison pipeline, but for a Black immigrant that doesn’t end in prison. They just sort of attach another piping that leads to deportation.”

In an investigation for Vox, the writer Shamira Ibrahim details the way that America’s interlocking systems of deprivation, criminalization, and punitive immigration enforcement have played out in the life of Ousman Darboe. Darboe is a 26-year-old immigrant from The Gambia who has been in detention fighting deportation for over three years now.

After being brought to the Bronx by his parents when he was only 6, Darboe attended a high school in the Bronx notorious for police presence in its hallways. A series of encounters with law enforcement as a juvenile — including for stealing a purse, marijuana possession after a stop-and-frisk, and theft of a cell-phone — landed him in Rikers Island just after his 18th birthday, where he spent nearly ten months in solitary confinement.

Shortly after being released, Darboe was accused of robbing a gold chain from a neighbor. Despite claiming his innocence, eventually he agreed to take a plea deal for time served rather than continue to fight his case from jail.

But the arrest brought Darboe into the crosshairs of ICE. Agents showed up at his parents’ apartment in February 2017 under false pretenses, detained him, and put him into deportation proceedings. In response to public outcry, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo pardoned Darboe for his robbery conviction earlier this year, but ICE maintains that it has the right to deport him for overstaying his visa anyway.

Without his contact with law enforcement — largely a result of the schools he attended and the neighborhood he grew up in — it’s unlikely Darboe would have come to the attention of ICE to begin with.

“We are setting up Black communities, and the Black immigrants who live in those communities like in the Bronx, to fail,” said Sophia Gurulé, Darboe’s attorney and a policy counsel at Bronx Defenders. “He was basically plagued by constant policing and criminalization since he was a teenager.”

Now, Darboe faces the prospect of deportation back to a country he barely knows, and where he could find himself ostracized from society.

“He’s been incarcerated for three years by ICE, and the last six months of that have been COVID. He’s now in solitary confinement for 16-18 hours a day — because everyone is — and his mental and physical health is truly deteriorating,” said Gurulé. (Precautions related to the pandemic have made conditions inside detention facilities even worse than usual, with long periods spent locked inside cells and restrictions on visits from lawyers and family.)

Cases like Darboe’s have started to raise awareness over the links between the issues faced by Black immigrant communities and those that spurred the Black Lives Matter movement. That solidarity is a welcome development, said Paulos:

“What the Floyd uprising did for Black immigrant communities that might have been isolated or segregated from Black American communities was that we all are starting to see that we’re getting arrested together and locked up together, and it’s high time that we started fighting together.”

Ashoka Mukpo, Staff Reporter, ACLU

Date

Thursday, September 3, 2020 - 2:30pmFeatured image