This week, the presidential candidates will face off in their first debate of the general election. Voters will hear Donald Trump and Joe Biden talk about their views on the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy, and the Supreme Court vacancy created by the untimely passing of ACLU alumna Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The ACLU and our supporters will be listening closely for how their answers relate to key civil liberties issues, including racial justice and reproductive freedom, just as we have throughout the presidential campaign.

This cycle, the ACLU has gotten involved in the presidential campaign in a serious way for the first time. During the primaries and caucuses, our volunteers spread across the early states to get commitments (on camera) from the candidates of both parties, on issues like access to abortion and immigrants’ rights. In fact, it was our volunteer, Nina Grey, who secured the all-important commitment from Joe Biden to end the Hyde Amendment, which has blocked access to reproductive health care to low income individuals for decades.

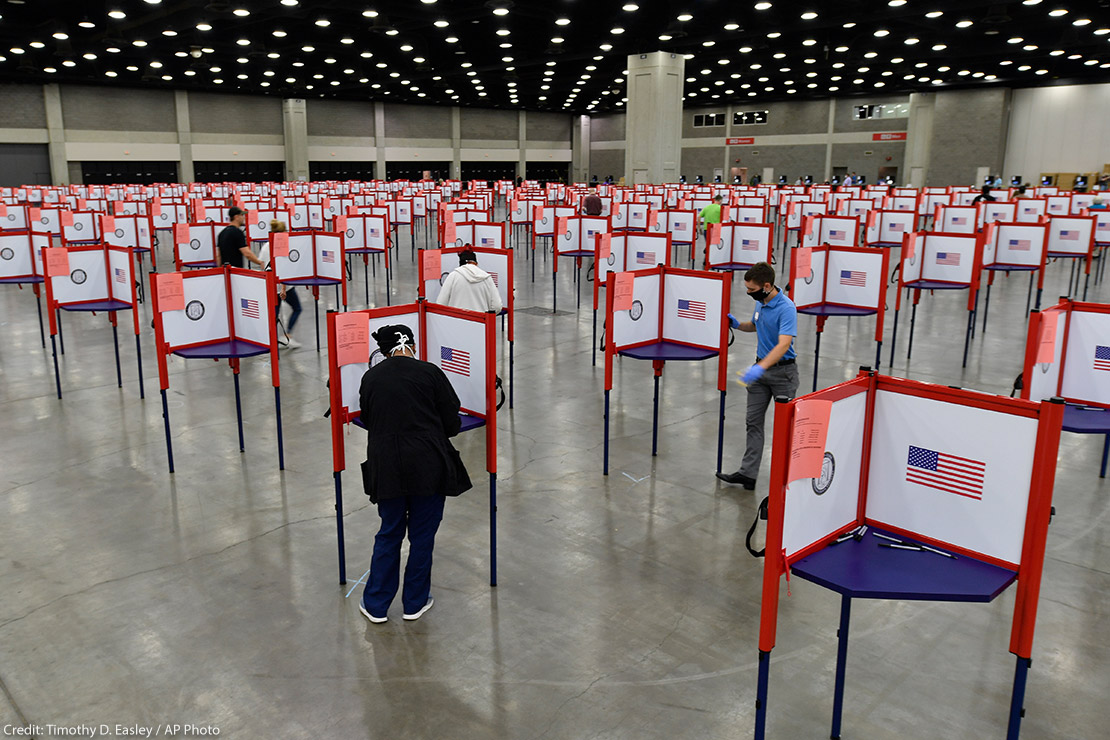

Now, as we enter the thick of the general election, we’re not backing down. Instead, we’re making sure every voter understands the civil liberties issues at stake, and knows how they can safely and effectively exercise their right to vote. Our message to voters: Vote like your rights depend on it.

In Michigan, we’ve launched a voter turnout campaign for the Presidential election, to build on the success of last cycle’s Proposition 3 Promote the Vote ballot initiative, which brought no-excuse absentee voting and same day voter registration to the state. We are ensuring that voters — particularly Black Michiganders, young people, and other populations positioned to benefit from the ballot measure — are educated on their rights and options, and encouraged to get to the polls. We are running a parallel voter turnout program in the other important presidential battleground of Wisconsin.

We are also continuing our commitment to down-ballot races that often have the greatest impact on policies and practices that affect civil rights. Our focus on hyper-local races, like sheriffs and district attorneys, has brought about crucial improvements on bail reform, reductions in prison and jail populations, protections in access to abortion, and the end of immigration detention agreements with the federal government. Voters have the opportunity to usher in even more change in this vein on Nov. 3.

In the 2020 ballot measure space, we’ve made racial justice one of our top priorities for this election cycle. Our largest financial and personnel commitments have focused on three ballot referenda with strong racial justice implications. In California, the ACLU and its affiliates will invest approximately $1 million to lift a ban on affirmative action. In Oklahoma, we have spent more than $3 million to enact far-reaching criminal justice reforms that will help address racial biases and systemic inequality in the criminal legal system. In Nebraska, we’ve invested over $1 million to fight the extortionist practices of predatory payday lending institutions, which takes $28 million a year from low-income people, disproportionately people of color, in the state. Taken together and coupled with another ballot measure investments, the ACLU is flexing its political power to advance an agenda of systemic equality — one that gets at the root causes and persistent effects of systemic racism.

We are a nonpartisan organization, and we don’t endorse or oppose particular candidates for office. But we’re involved in elections because the stakes are incredibly high for civil rights and civil liberties issues in America. The ACLU aims to educate voters about the civil liberties and civil rights records of candidates — through paid and earned media and other forms of voter communication — and encourage voters to factor those records into how they vote. At the same time, we mobilize ACLU volunteers to ensure that Americans around the country understand the potential consequences of these elections, certainly the most consequential in generations in terms of civil liberties and civil rights. Our volunteers will make millions of phone calls and send millions of text messages to voters over the course of this election. And through our new platform, Let People Vote, we’re ensuring people know how and when to vote, as well as how to get involved in their state.

The ACLU takes its nonpartisan status very seriously. We are not nonpartisan merely out of tradition or to protect our tax status; we are nonpartisan because our commitment to civil rights and civil liberties drives everything we do. We have an issue-based agenda, not a party-based one. We are nonpartisan because we have had allies from all political stripes and all political parties — and opponents, also, from all points on the political spectrum. Rather than judge politicians based on their party affiliation, we judge them on their civil liberties and civil rights records and stances. We thanked Chuck Grassley — the Republican senator from Iowa — for his leadership on the First Step Act with a full-page ad in his local newspaper. And yet, we are likely to clash horns with the same Senator Grassley for refusing to defer the confirmation process for Justice Ginsburg’s successor until after inauguration. We are an equal opportunity friend and foe, but a constant advocate for civil liberties and civil rights. When we engage in politics, we do so to highlight the issues that affect our daily work and the lives of millions of Americans.

Success for us is infusing a higher profile discussion of key civil liberties issues into elections and into voters’ calculus when casting their votes. We engage in electoral work because this is when citizens are most engaged, our issues are most salient, and voters have the greatest power to affect policy. It is also when politicians are most likely to take seriously what voters care about. Our goal is to make sure candidates know civil liberties and civil rights issues matter to voters and move the needle on key policies and practices.

We’re trying to change hearts and minds on civil liberties issues, and therefore we have short- and long-term goals. For instance, an anti-civil liberties candidate may very well win despite our best efforts to educate voters about that race, but we will have fulfilled our mission if we’re able to increase voters’ understanding and awareness of civil liberties issues.

We, therefore, have made and remain committed to the following assurances about our electoral work:

The ACLU will not endorse or oppose specific candidates for elected office. Our goal is to ensure that voters are educated about the potential consequences of an election, not to support specific candidates.

The ACLU will not tell people to vote for particular candidates. Educated voters can make their own decisions. The ACLU’s job is to provide voters with the information they need to know about what is at stake.

The ACLU will not coordinate with any partisan organization in electoral work. While the ACLU believes deeply in working in coalition with other nonprofits, we have no interest in partisan coordination. Our aims are different from those of a political party, and are driven by issue-based goals. (We know, for instance, gerrymandered political maps that disenfranchise voters have been drawn by both Republicans and Democrats — and we have opposed them in both instances.)

The ACLU will let civil rights and civil liberties issues drive its electoral work. The ACLU is not doing electoral work to affect the balance of political power, but to drive concrete policy outcomes that matter for people’s lives. We will choose to engage in electoral races where important civil rights and civil liberties issues are at stake. And we aim to establish a mandate for politicians to enact policies that expand rights and freedoms for all. For every election we participate in, we will be able to identify a set of concrete policies and practices that have changed because of our electoral engagement and the ultimate decision of the voters.

The ACLU will aim to educate voters about the consequences of specific elections. This could include issuing scorecards, hosting ACLU-sponsored issue-based town hall meetings, doing issue-focused radio ads or TV, mailers, billboards, or transit ads. The goal is to infuse a discussion of civil rights and civil liberties into a political race and to communicate to the public how the choice of elected officials leads to differences in policies and impacts on people’s lives.

The ACLU will urge voters to go to the polls. It does not matter how much voters understand about an election if they do not vote. In the end, the choices that people make on Election Day have great consequences. The ACLU will encourage voters to make their voices heard.

The ACLU will defend election integrity and ensure that every vote is counted, regardless of the party affiliation of the voter. In addition to our advocacy to inform and turn out voters, we engage in advocacy and litigation to ensure that every vote counts. This includes 31 lawsuits in more than 20 states, as well as pressing for laws in states like North Carolina to ensure that voters who have their mail ballots rejected have an opportunity to “cure” or fix them. With offices in each and every state, and boots on the ground in every voting jurisdiction, the ACLU is uniquely situated to ensure that every vote is counted in this critical election.

Electoral work in this frame is a natural extension of the work we have been doing for 100 years. The ACLU has never shied away from a fight when civil liberties were at stake, whether that fight was in a courtroom, Congress or a state legislature, in the streets, or at the ballot box. We ask you to join us in this important endeavor.

Ronald Newman, National Political Director, ACLU

Paid for by American Civil Liberties Union, Inc., 125 Broad Street, New York, NY 10004, and authorized by Nebraskans for Responsible Lending.

Authorized and paid for by American Civil Liberties Union, Inc., 125 Broad Street, New York, NY 10004, 212-549-2500, on behalf of Yes on 805, Inc.

Paid for by American Civil Liberties Union, Inc. (major donor committee ID # 1259514) and authorized by Yes on 16, Opportunity for All Coalition, Sponsored by Civil Rights Organizations.

Date

Tuesday, September 29, 2020 - 10:30amFeatured image