Eva Lopez, Communications Strategist, ACLU

Leila Rafei, Former Content Strategist, ACLU

Like other essential workers, domestic workers are bearing the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic without the luxury of being able to telework, social distance, or even take a sick day. They also face unique and challenging circumstances due to the nature of their work, which is undervalued and under-regulated by the U.S. government. As a result, domestic workers often endure horrific abuses that go unchecked. Many are brought to the U.S. by employers promising a better life, only to find themselves subjected to forced labor, denied wages, and threatened with deportation.

Today, the ACLU and the Global Human Rights Clinic joined a coalition of workers’ rights organizations calling on the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to acknowledge and address the U.S. government’s failure to protect the rights of domestic workers. These workers are overwhelmingly women of color and/or migrants, and include house cleaners, nannies, caregivers, and others who work out of public view and in their employers’ homes. Below, four domestic workers explain in their own words the all too common abuses that continue unheeded because of the government’s failure to act.

FAINESS

My trafficker was a Malawian diplomat to the U.S. I had known her for years back home in Malawi, where I worked for her as a nanny before coming here. When she was stationed in D.C., she asked me to come with her, promising better opportunities — I could get an education, get a better job, get out and see the world. As a young person, what else could you want? She gave me a contract and travel documents and rushed me to sign them even though I could not speak or understand English at the time. After I was granted an A3 visa, which is a special visa for diplomats’ domestic workers, we left for the U.S., where we moved into a home in a beautiful neighborhood in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Everything changed when we got to the U.S. My trafficker was no longer the person I knew in Malawi — she turned into a tiger. She forced me to work more than 16 hours per day for less than 40 cents per hour, cooking and cleaning and doing laundry, even ironing the family’s underwear. Who does that?

I lived in my trafficker’s home, but not as an equal. I lived like a slave.

I lived in my trafficker’s home, but not as an equal. I lived like a slave. She made me sleep on the basement floor and forbade me from using any of the family’s soaps or other items, so I would not “contaminate” their belongings. She cut my phone access, so I was not able to communicate with my family at all for three years. I was refused medical care when I was sick. The only food I could eat were leftover scraps. Many times, I had to watch the family eat while I was starving and malnourished.

While I lived there, I was raped by a family friend. I could not receive any help because I did not speak English and did not know what to do. Whenever I tried talking to my trafficker about anything, she would call me ungrateful because she had taken me from my poor home village. Often, she would say “I can do anything I want, I’m a diplomat, I have immunity.” She also accused me of sleeping with her boyfriend.

The pain was too much. I was dying slowly, and I could not take it anymore. I wanted to die, but I knew that if I died in that house, my trafficker would throw my body in a dumpster and no one would ever find out. So I thought maybe, if I die in the street, people will find me and my family will learn of my death, maybe on the news.

One day, I found my passport and snuck out of the house through the garage. I was so thin, I managed to squeeze myself through the gap beneath the garage door. Then I ran away, leaving everything behind.

It’s our pain and our story. You cannot fight trafficking without survivors, period.

Today, I am a survivor. What happened to me doesn’t define me. While I still have not overcome my traumas 100 percent, I empowered myself through learning about who I am, my rights, and trafficking laws. I learned that trafficking is not just sex trafficking, and it was labor trafficking that brought me to the U.S. and entrapped me. Now I am a leader. I am a member of the National Survivor Network and a board member of the Survivor Alliance. I have spoken before Congress and at conferences. I work alongside NGOs to change policies, including a labor statute in Maryland that I advocated for.

Still, I am angry that domestic workers are invisible to many people. The whole time I was suffering, nobody saw me. I remember shoveling snow in my trafficker’s driveway, without gloves, boots, or warm clothes, watching cars pass as everybody missed those red flags.

It’s hard to identify trafficking of domestic workers since it usually happens behind closed doors, but the community should learn how to identify these situations and hold labor traffickers accountable. Domestic workers deserve fair treatment, decent pay, and benefits. The government, Congress, and our communities need to make sure survivors always have a seat at the table. Nothing about us, without us. It’s our pain and our story. You cannot fight trafficking without survivors, period.

CARLOS

When I first came to the U.S., I didn’t realize I was being trafficked or that my working conditions were not normal. I had come here for the same reason as a lot of Filipinos — a simple dream, especially as a father, to bring my family out of poverty. I didn’t know about my rights. All I knew is that I came here to work. I was just so happy and excited to be in America.

Before I came here, an employment agency in the Philippines found me a job as a cook at a country club in Florida. I had to pay them $3,000 just for all the paperwork to get here. Once I arrived, I stayed in a small house with a bunch of other workers, about six or seven of us in each room. I thought it was all normal. I believed in the lies my employers told me about the contract, the salary, the house, the visa. They told us we would get green cards and be able to bring our families here.

After working for a few months in Florida, they moved us to another country club in Arkansas. They told us our visas had expired, so there was no contract and no paycheck, just a cash advance of $500. My pay was only enough to cover my basic needs in the U.S. I had no money left over to send back home to my family.

They threatened that if we tried to leave, they would call the police and report us to immigration. The treatment was so bad that some of us ran away anyway, but I was too afraid of being deported. I said to myself, I’m here in America for my family. They were still suffering so much to get food on the table. All they could afford to eat was rice and soy sauce.

They threatened that if we tried to leave, they would call the police and report us to immigration.

One night I decided to do it. I got on a Greyhound bus at 3 or 4 a.m., with just my passport and $500 in my pocket, and traveled from Arkansas to Texas, where I stayed with my aunt for a little while until my uncle found me a job in California. I took that job, but it ended shortly after. I had no work for three months. I felt homeless and that I had ruined my family. That’s when I became an alcoholic. I wanted to be drunk all the time, to fall asleep and forget everything that had happened in America. Every time I try to remember everything, it all comes back to me, all the depression and fear.

I thought about going home, but I knew I could not go back to the Philippines for a very long time. I told myself I was already here and that I needed to be patient. Back home we call America the land of opportunity. At that moment, I didn’t know if I could call America that, but I never surrendered or stopped looking for a job. I kept fighting for my family. The only thing I had to hold onto was my faith. I prayed that one day it would all be okay.

My life restarted again when I found a job as a cook and housekeeper in a big house in Beverly Hills. Now I am in another job, working as a caregiver. I still have anxiety every time I see police and fear being caught. I still have trouble sleeping. But I got help for substance abuse and treatment for my depression and anxiety. Today, the trauma is still there, but it’s not as heavy anymore.

It has been 13 years since I was home in the Philippines. I still have hope to bring my family here and get a fresh start. I don’t want what happened to me to happen to my children.

SAM

For me, coming to the U.S. was the realization of a dream, not only for myself but for my family. I was a physical therapist in the Philippines so I was really happy when an employment agency got me a job doing the same work in the U.S. But when I got here, it was nothing like they promised. We were thrown into a hotel in a rough neighborhood. There was no work, no visit to the jobsite, no employer nor a representative who came to welcome us and see how we were doing. We were left on our own. We survived for 14 days eating noodles from the 99 cent store.

I endured the treatment because I had no choice and I didn’t know the laws in the U.S. It was tormenting and traumatic being in a foreign land with no knowledge of the laws, specifically laws about employment and immigration. I also didn’t know before I came that I would have very, very limited job choices as an undocumented immigrant resulting from my trafficking. Living in fear of being deported was stressful and suffocating. Even more because I cannot afford insurance or medical care so I had to just take vitamins and pray to God, and by God’s grace I was able to stay well.

It was tormenting and traumatic being in a foreign land with no knowledge of the laws, specifically laws about employment and immigration.

I learned a little from a childhood friend who has been a U.S. citizen for a long time and also works as a physical therapist. He told me that he learned about four physical therapists who had reported their agencies for violations of human trafficking and that they won their cases and got justice. At the same time, my Filipino values of perseverance and faith somehow deterred and delayed me from seeking help for myself.

Information about domestic workers’ rights and human trafficking abuses should be readily available to immigrant communities. It should be easy for workers to contact authorities, even their local embassies, and get help. Labor rights should be plainly black and white and both employers and employees need to adhere to them. There should be a collaboration between the host country and the country of origin of trafficking victims so these predators are stopped from the very beginning. We must treat each other with respect and humanity. We are human beings too and not just nominal subjects for profiteering.

MELANIE

I came to the U.S. from the Philippines to support my family. One of my children had cerebral palsy and was prone to pneumonia, and was always in the hospital, which was expensive. I could not afford his treatment. So when I found an opportunity for a job abroad, I tried my luck and took it.

An employment agency in the Philippines connected me to a job in a chicken factory in Washington State. To get here, I had to pay the agency $5,000 plus airfare. All the problems started when I arrived. The agency told me and other Filipino workers it would cover housing, but when we got there we found out we had to stay in another employee’s home for the first three weeks, and during that time we had to do her housekeeping and take care of her three children, on top of going to work at the factory. Finally they moved us to a housing unit. We were 20 people with one bathroom and no furniture. The women slept in the attic, about 10 of us.

Working at the factory was difficult and dangerous. My job was to debone chicken with an electric sensor on a conveyor belt. We had to work fast, which made it hard to protect ourselves. Fingers were always being cut. There were also immigration raids so we were in constant fear of being caught and deported. I had a visa, but some of the other employees did not have papers. All of us were afraid.

After six months, the company let us go even though our contracts were for a year’s work. Some of my other coworkers from the Philippines were afraid they would lose their visas from being out of work, so they went home. I missed my family and wanted to go home, too. I wanted to provide for them but at the same time, I have to pay my debt. I am still paying off the loans I borrowed to pay the employment agency fees.

Domestic work is seen as a lowly job but it’s a decent job and it’s vital to society. We should not be ignored. We are important.

In the Philippines, we have this idea that going to America will bring you a bright future. So even though I wanted to go home, I knew people would treat me like a failure if I did — I had been planning to bring my family there and I had failed. All of a sudden you’re back with nothing but debt. People think only criminals get deported. So I stayed.

To get another job, I had to pay the agency a $500 processing fee and they placed me at a resort in Sedona, Arizona. Our living conditions were better there, but the work was physically exhausting. We worked in teams of two to clean 20 rooms per day. I got sick with high blood pressure and vertigo, which made it very difficult to continue working, but I didn’t go to a doctor because it was expensive and I didn’t know about insurance. I decided to resign, but when I told my employer, he threatened to deport me. I ended up staying for three months before I finally broke free. Then I started looking for another job, one that would not take a toll on my health.

My friend found me a job as a caregiver in California. That’s where I live now. I share a place with a senior who needed help paying rent. I spend most of my salary on phone cards calling home, and while the job is steady, the landlord threatened to evict me because I am not on the lease. California’s eviction moratorium has prevented that for now.

I came here to support my family, but I am still trying to save up enough money to see them. My son passed away from his illness last year and I was not able to be there. Many times, I wished that I never came here, that I never had to go through what I did. Had I known that what my traffickers had promised were lies, I would have stayed in the Philippines in the first place.

All I want as a domestic worker is recognition. Domestic work is seen as a lowly job but it’s a decent job and it’s vital to society. We should not be ignored. We are important.

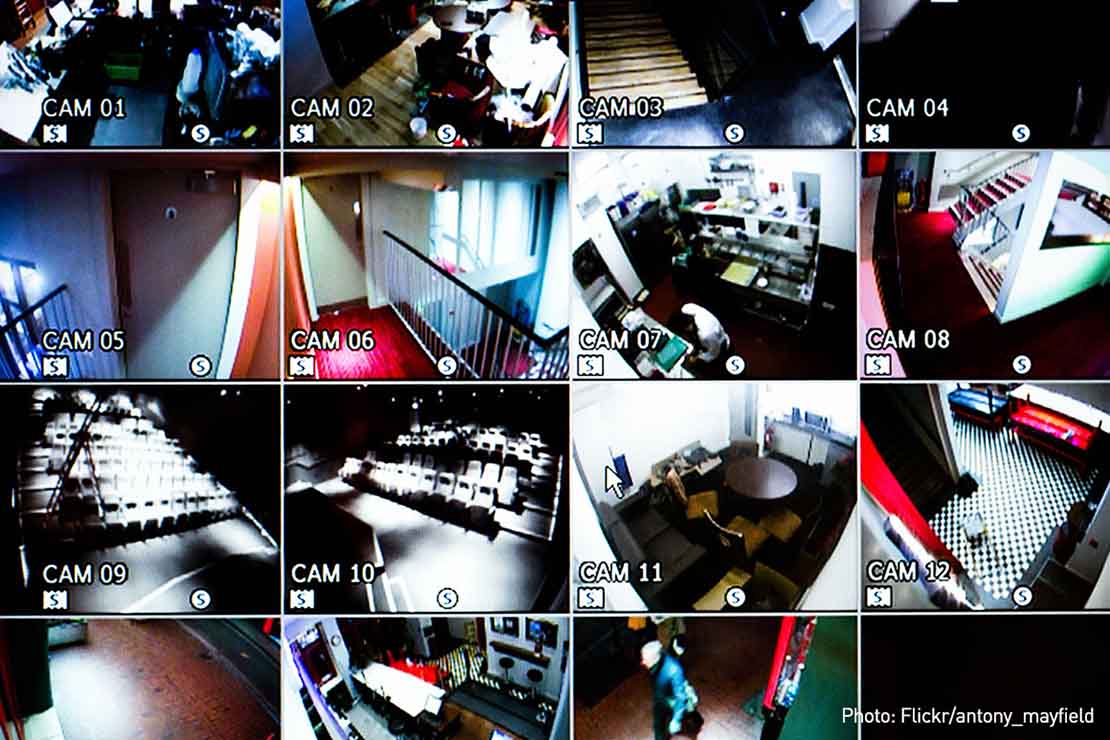

There are potentially thousands of domestic workers living across the U.S. right now, who have been trafficked and forced into labor while being subjected to many of the same inequalities other essential workers face. In fact, COVID-19 has only laid bare the dangers and abuses of domestic work that long predate the pandemic: low wages (often below local minimum wages), overwork, unhonored or nonexistent contracts, employer surveillance, lack of access to healthcare, and more.

The petition was filed by the ACLU and the Global Human Rights Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School. It demands immediate action to address these abuses, and draws from the expertise of four individual domestic workers as well as workers’ rights organizations including National Domestic Workers Alliance, Adhikaar, Damayan Migrant Workers, Centro de los Derechos del Migrante, Human Trafficking Legal Center, Fe y Justicia, and Pilipino Workers Center.

https://www.aclu.org/news/immigrants-rights/behind-closed-doors-the-traumas-of-domestic-work-in-the-u-s

The U.S. government's failure to act has allowed domestic worker abuse to continue unchecked.