“This guy is pretty much scalped over here. This guy, he’s breathing but I couldn’t get a pulse on him. I think he’s going,” a Border Patrol agent is heard saying on Doña Ana County Sheriff’s Office body cam footage from August 3, 2021. Early that morning, Border Patrol agents pursued a vehicle at high speeds on a narrow road, causing a crash that killed two people and injured eight others.

One of those who died following the August 3 crash was Erik Molix, a U.S. citizen whose parent is now our client. Between 2019 and 2021, the number of deaths resulting from Border Patrol vehicle pursuits jumped 11-fold, to 23 deaths last year. The body count for such chases continues to increase this year. The agency’s deadly actions raise urgent questions about how these pursuits are investigated and what measures are taken to ensure public safety and accountability.

Of particular concern has been the involvement of Border Patrol Critical Incident Teams (CITs). For the first time ever, we were able to obtain a copy of the incident report produced by a CIT following a fatal incident. That report, on the August 3 crash, is littered with inconsistencies and inaccuracies, revealing how CITs operate in a way that could obfuscate the facts of the incident and protect the Border Patrol and its agents from accountability.

This report proves that ending CITs, as U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has announced it will do at the end of this fiscal year, is not enough. The agency must preserve all past records created by the CITs and initiate an independent review of cases impacted by CIT involvement.

Investigators Charged with Protecting their Own

Customs and Border Protection, Border Patrol’s parent agency, has a long history of allowing personnel to commit abuses with impunity. The agency’s disciplinary system has long failed to secure appropriate outcomes for misconduct. At the center of the internal system to review agents’ misconduct and issue disciplinary consequences is the CBP Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR). While OPR is tasked with conducting independent and impartial investigations, confidence in their results is wholly undermined by the involvement of Border Patrol’s CITs as investigators.

Documents uncovered by the Southern Border Communities Coalition last year revealed the existence of CITs, whose stated mission is the “mitigation of civil liability” for Border Patrol agents who might face lawsuits for misconduct. CITs report to Border Patrol leadership at the sector level and are tasked with conducting investigations of “any traffic collision” and any Border Patrol conduct that “results in death, serious bodily injury, significant property damage, or other exposure to significant civil liability.” These teams, which do not operate independently or impartially, have a clear bias and conflict of interest when they are charged with investigating incidents where agency personnel may prove to be liable for misconduct.

Our client walks where her son was killed with ACLU of Texas Staff Attorney Shaw Drake.

Credit: Sharon Chischilly

Troublingly, CITs are not designated by the U.S. Office of Personnel Management as criminal investigators and are not authorized to undertake any such investigations. All other federal agencies tasked with the investigation of potential criminal misconduct operate under explicit statutory authority. The U.S. Department of Justice’s own standards and guidelines for internal investigations further instruct that only allegations of minor misconduct, such as “discourtesy or rudeness,” should be relegated to the “unit level,” with oversight by the authorized internal affairs office.

James Tomsheck, head of CBP Internal Affairs from 2006 to 2014, stated in court documents published in 2021 that Border Patrol “had no authority to investigate, but it nonetheless consistently tried to assert investigative authority, and very frequently interfered with legitimate investigations,” adding that, “It was standard practice for Border Patrol to defend incidents in use of force, to always make it appear that it was justified.”

Little is known about CITs’ activities in cases involving deadly vehicle pursuits, beyond their apparent mandate within the agency to investigate such incidents. We were only able to confirm the direct involvement of an El Paso Sector’s CIT in investigating the recent crash that killed our client’s son by way of state-level public records requests — and the CIT report for this crash raises more questions than it answers.

Deeply Flawed CIT Investigation of Deadly Crash in New Mexico

The CIT report for the August 3 incident is the first of its kind obtained by advocates investigating CBP accountability. It provides us with unprecedented insight into how CIT investigators process a scene and the quality of the reporting that they generate, upon which OPR and other investigators rely.

The 162-page “Report of Investigation” indicates that the CIT played the central role in investigating the deadly crash. The CIT responded immediately, deploying investigators to the scene of the crash as well as the regional hospitals where victims had been transported. They photographed the crash, collected physical evidence, obtained video recordings and radio communications, interviewed and photographed the victims and Border Patrol agents involved, obtained reports from New Mexico State Police and the El Paso County Office of the Medical Examiner, and analyzed the evidence gathered from the scene. Their investigators reconstructed the crash and calculated the vehicle’s estimated speed.

Troublingly, the CIT report is riddled with errors, gaps, and inconsistencies that fundamentally undermine the investigation.

The report contains multiple inconsistent narratives that purport to describe when and why a Border Patrol agent initially began to follow the victims’ vehicle as it approached a Border Patrol checkpoint on NMSR 185, in rural southern New Mexico, and the CIT investigators make no effort in the report to identify or reconcile those discrepancies. The report’s summary says that the agent initially followed the vehicle “at a distance,” but when the vehicle passed the checkpoint the Border Patrol agent was, according to the CIT investigators’ summaries of video recordings, only 0.04 seconds behind the vehicle.

The report is unclear about when the Border Patrol agent following the vehicle activated his emergency equipment, which is a critical data point because CBP policies regarding vehicle pursuits only apply when an agent activates their lights and sirens. The agent reportedly did not activate his emergency equipment until after the vehicle bypassed the checkpoint, even though he was already following the vehicle extremely closely. Some of the vehicle’s passengers reportedly only saw emergency lights but did not hear sirens, but the investigators make no mention of whether recordings indicate if both lights and sirens were in fact activated. Both are mandatory under CBP’s vehicle pursuit policy.

Additionally, summaries of video recordings in the report indicate that Border Patrol agents at the checkpoint set out “spike strips” to attempt to stop the vehicle, but the E-STAR Incident Report states that no such devices were deployed. Again, the CIT investigators make no note of this discrepancy.

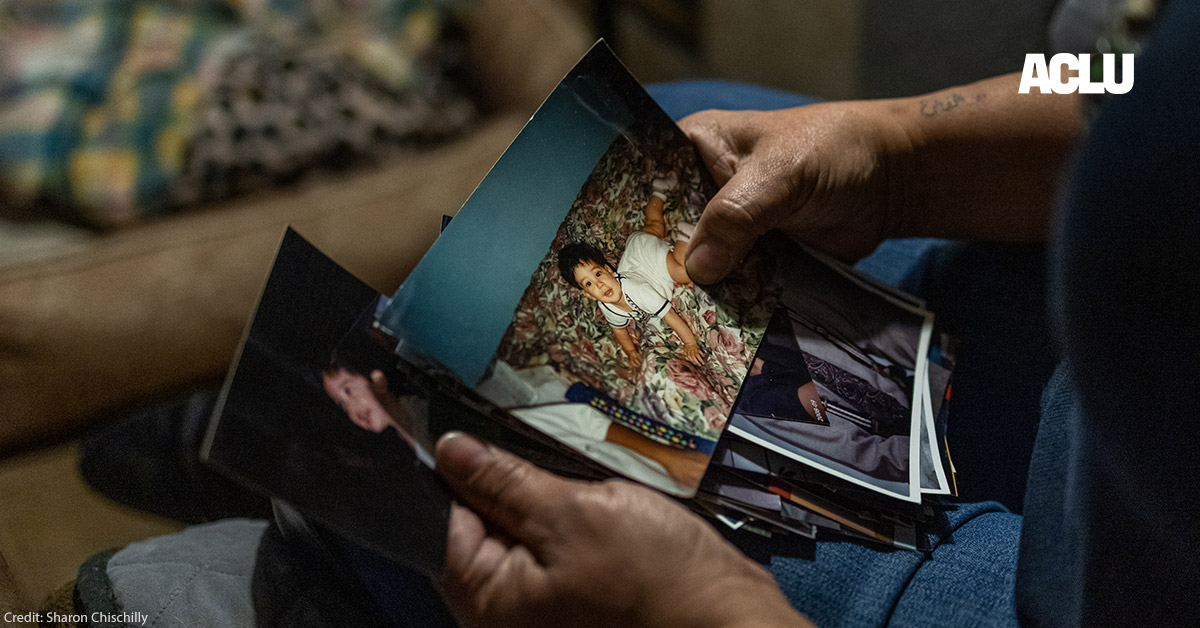

A photo of victim Erik Molix.

Credit: Sharon Chischilly

The circumstances of the crash are likewise unclear and the report does not provide any critical analysis of gaps and inconsistencies in the record. The last radio transmission by the agent who initiated the pursuit was at mile marker 27, but the crash did not occur until approximately mile marker 28.5. What transpired in the intervening mile and a half is not clearly accounted for. The CIT investigators’ summary of the incident states that the “pursuit” lasted about 3.2 miles, but the Border Patrol checkpoint is only approximately 2.5 miles from the crash site. The Significant Incident Report provides yet another inconsistency without explanation, stating that the pursuit only lasted about 1.5 miles. Remarkably, the latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates in the E-STAR Incident Report indicate that the pursuit started at the Border Patrol checkpoint and ended in a location off a country road that is 38.6 miles away. The same Incident Report states that the pursuit lasted 2 minutes and traversed 2.5 miles. The crash is attributed varyingly to high speeds on a curve in the road and to the vehicle “being overloaded.” The report alternates between characterizing the incident as a “collision” and as a rollover.

The report fails to scrutinize statements addressing how promptly the Border Patrol agents called for emergency medical services. The CIT investigators’ summary states that agents “immediately” requested EMS, but time-stamped radio logs in the Significant Incident Report indicate that EMS and medical airlifts were not requested until 10 minutes after the crash. The report’s transcription of radio communications, which lacks timestamps, indicates the urgency of the situation, with an agent on the scene stating that “most” of the vehicle’s occupants were “nonresponsive” and saying, “Give me as many ambulances uh that you can send.” Injuries ranged from brain damage and skull fractures to spinal fractures, hematomas, and lacerations. One passenger’s scalp was ripped off, multiple individuals had to be intubated, and two ultimately died.

The report makes clear that CIT investigators were among those first notified of the incident. Within 20 minutes of the crash, Border Patrol personnel reached out to the CIT, and a CIT investigator was en route to the scene from El Paso about half an hour later. Another CIT investigator went directly to the regional hospital to meet the air ambulance there. It is not apparent from the report when OPR was first notified. The report indicates that one of the CIT investigators met with an OPR Special Agent in Las Cruces on the day of the incident and OPR conducted some interviews. The report does not contain information indicating whether CIT investigators conducted interviews alongside OPR or otherwise.

The photographs that CIT investigators took of the incident are wholly inadequate in providing clarity about the crash. The photographs at the scene of the crash do not have a timestamp. The photographer was standing at a distance from the vehicles parked on the roadway, such that no license plate numbers or unit numbers are visible, other than for the vehicle that crashed. The report does not include any photographs of the places on the roadside where people who were ejected from the vehicle were located. Subsequent photographs taken of the vehicle’s driver and passengers, many still hospitalized, do not have names, locations, timestamps, or other identifying information.

The photographs of the Border Patrol vehicles involved in the pursuit are, inexplicably, not from the scene of the crash. They were taken at night, in a parking lot with poor lighting, and one vehicle is partially covered by the shadow of the photographer. The Border Patrol vehicles appear to have been recently cleaned. One of the Border Patrol vehicles was also photographed in what appears to be an automotive repair shop on a lift. These, too, lack any timestamps, although the report indicates that CIT investigators did not request photographs of the Border Patrol vehicles involved in the incident until August 9, six days after the crash. No explanation for the delay is provided and raises questions about any potential contact between the Border Patrol and victims’ vehicles.

Other inconsistencies and gaps in the report further call into question its reliability. The report does not indicate a chain of custody for any evidence collected but confirms that the photographs, diagrams, audio recordings, and video recordings of the incident are all archived by the El Paso CIT. A checklist of required notifications does not indicate that any photographs were collected, although the report itself contains photos taken at the scene. That same checklist does not indicate that any administrative claim forms for damages, injury or death were distributed, despite the multiple deaths and severe injuries incurred by the vehicle’s occupants. One part of the report says that the U.S. citizen driver was arrested at the time of the crash, but another part of the report says that he was not arrested or taken into custody. The report erroneously states that the driver died of his injuries on August 16, when in fact he was pronounced deceased on August 15.

The report does not provide detailed information about the custody determinations and immigration processing for the vehicle’s passengers, but it does indicate that at least two individuals were rapidly expelled from the United States under Title 42. Those expulsions took place only a few days after the incident, while the CIT investigation into the crash was ongoing. Notably, the CIT report includes a copy of a newspaper article regarding a letter sent by the ACLUs of Texas and New Mexico to CBP calling for an independent investigation into this incident. When victims and witnesses are expelled by CBP, the same agency conducting the investigation into an incident involving its own agents, it raises serious questions as to whether those individuals were denied access to legal protections or remedies that may have been available to them as a result of CBP misconduct.

Fundamentally, the CIT report of the August 3 vehicle pursuit and crash demonstrates the need for the agency to preserve all past records created by the CITs and initiate an independent review of cases impacted by CIT involvement. If this report is indicative of the standards at which CITs perform, OPR has jeopardized the independence of past investigations by relying on documentation of such dubious accuracy for serious incidents involving injuries and deaths.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the origin of the body cam footage from the crash scene. The footage is from a Doña Ana County Sheriff’s Office’s body camera.

Date

Tuesday, June 7, 2022 - 1:15pmFeatured image