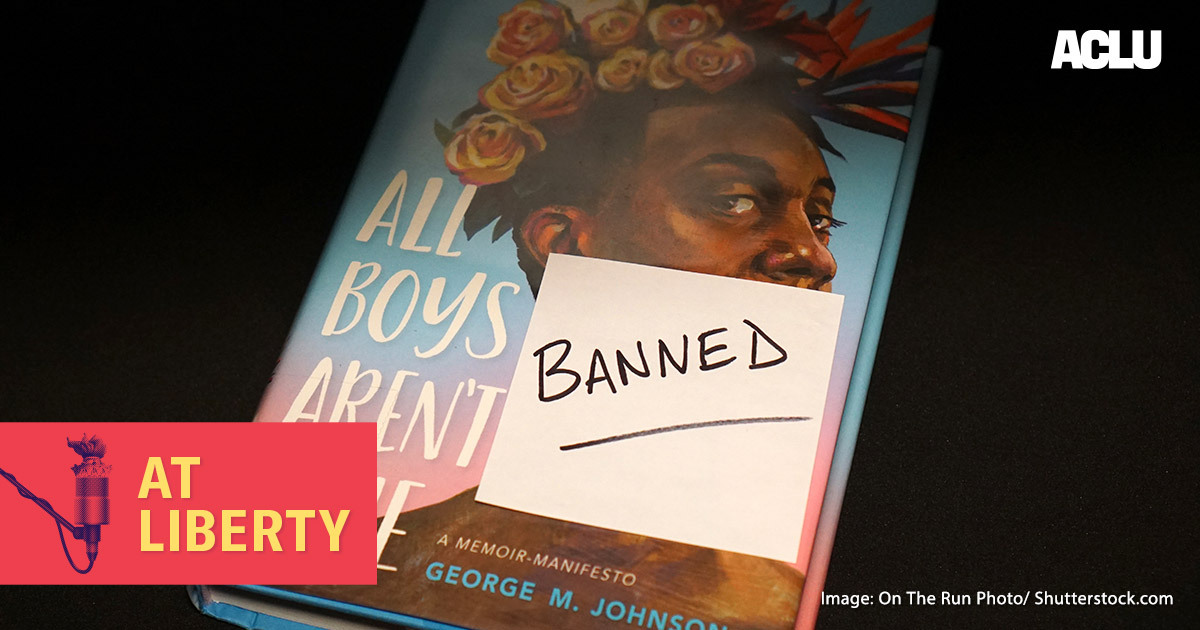

Over the past two years, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of books being banned or challenged in school districts across the country. The majority of the stories that are being censored contain LGBTQ storylines and protagonists of color, including All Boys Aren’t Blue, a story about growing up Black and queer in New Jersey and Virginia and one of the top five most banned books in the country. The author, George Johnson, joined At Liberty this week to talk with us about what makes Black queer voices so threatening, the unique power of books, and their resolve to remain true to their story despite the attacks.

Q: You’ve said in prior interviews that you always knew your book was likely to be banned. Why did you think that?

I just saw the landscape of the country we live in, and it seemed obvious to me that someone was going to take issue with my book. I had already seen rumblings around books like The Hate U Give, Dear Martin, and the 1619 Project. So as I was going through my process of writing the book, in my mind, I was like, “Okay, if they’re coming for those books, they’re definitely going to come for mine, too.” I knew the myriad topics I was covering in my book, including racism and anti-Blackness and sexuality, was not going to make a particular group of this country happy.

Q: Did that change or shape how you approached writing it?

No, I think it just made me [think], I might as well tell the truth. I might as well go all the way out with it. Because regardless of how I try to write this, frame it, sanitize it — which there were times I did think about sanitizing it — it wouldn’t have mattered. They were going to find issue with this book [anyway]. So it only inspired me to write it in its totality with full vulnerability and transparency.

Q: Many banned authors are among the most well-regarded in American literature. How does it feel to be among the company of your idols?

It’s bittersweet at times. I can’t believe they’re still attacking Black writing after all these years, but yeah, it feels great. When I’ve talked to those who have been in this industry for a long time, they’re like, “If you’re getting banned, you’re probably saying something really, really important, because look at the company you’re with.” And so I do take a lot of pride in it. It would be one thing if [the people trying to ban my book] were actually reading the story, but they’re not reading the story. They read the same four passages at every meeting. They’re always shocked when people bring up other passages and they’re almost like, “What book is that from?” Because [they] actually have never read the book.

Q: What do books give us that other mediums can’t, that makes them such irresistible targets for this kind of censorship?

Books stand the test of time. I think that’s pretty much it. Books are a time capsule. It’s not like a tweet that went viral that you may be able to pull up 10 years later … Toni Morrison’s books from the 70s, the 80s, they are still here. They are still widely being adapted. They’re still being turned into movies and films. When these books come into the world, they don’t go away. And I think that’s also the thing … You can block [students] for maybe two or four years from reading it in high school. But then they exit and can go grab it. Amazon doesn’t go away. It exists in multiple languages. It actually just makes [the book] more irresistible.

Q: Why are queer and Black stories so threatening and therefore so powerful?

Because they are an educational tool that builds empathy between communities of people who never knew that people outside of their bubbles exist. And I think that’s a real fear because Gen Z is the first generation in this country that’s more non-white than white. Generation Z is already identifying nearly 20 percent LGBTQ and they are going to be the next biggest voting bloc, as well as the next future senators, governors, presidents, and CEOs. If you empower them with the knowledge that other people exist outside of them … then they actually want to give equity and equality. I think that’s dangerous in the minds of the older generation of white men who continue to run this country.

Q: What would you say to people who have a story to share but are perhaps reluctant due to the climate that they would be publishing in?

When my ancestors had a story to share, the climate they were published in was extremely dangerous. You had slave narratives where they had to change their names, change some of their locations because of fear of being caught by slave catchers, even if they had moved to cities where slavery had already been abolished. So I think in every period of time in this country, [there have been times when] writing was dangerous. But I don’t think it should stop us from writing and telling our stories. It makes the landscape tough and it does make you more reluctant. But I think if you have a story to tell, you should just trust yourself enough to tell that story.

Date

Thursday, February 16, 2023 - 12:30pmFeatured image