The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) was enacted in 2008 to protect Americans from being widely discriminated against by a then new technology: genetic testing. The law was written after genetic discrimination emerged in the 1970s. At the time, programs to screen and identify genetic carriers of sickle cell anemia, a disease which afflicts many Black Americans, were being mandated by states. These mandated screening programs targeted Black people, perpetuating racial bias and stigmatization. Congress acted to make this genetic discrimination illegal. But now, GINA is 15 years old and needs to be updated to reflect a new threat of abuse of biological information — epigenetic discrimination. Because the law was written before many modern advances in the field of genetics, it is unclear whether its protections will extend to the novel types of information that will soon be generated from millions of Americans.

Technological and Scientific Advancements May Enable a Loophole in GINA

GINA was a culmination of more than a decade of work that began long before the entire sequence of the human genome was even known. GINA has enabled people to access their genetic information and undergo a genetic test without fear that the results would lead to higher health insurance premiums or lost work opportunities if that data showed them at risk of developing a disorder. It banned genetic discrimination, but only in the limited contexts of health insurance and employment.

But now it’s 2023, and we’ve learned much more about the human genome. While our DNA sequence (the identity of the A, C, T, G’s that make us who we are) has been made off-limits as a basis for discrimination by GINA, data about the environment around our DNA sequence can be used to infer, sometimes perfectly, the information about the DNA sequence itself. This environment around our genetics describes our epigenetics. Courts have not had an opportunity to address whether GINA’s language would protect against discrimination based on inferences about our genetic information made through analysis of our epigenetic information. We shouldn’t have to wait for discrimination to happen and lawsuits to get filed to ensure we have protection: Congress can and should make clear that there’s no loophole.

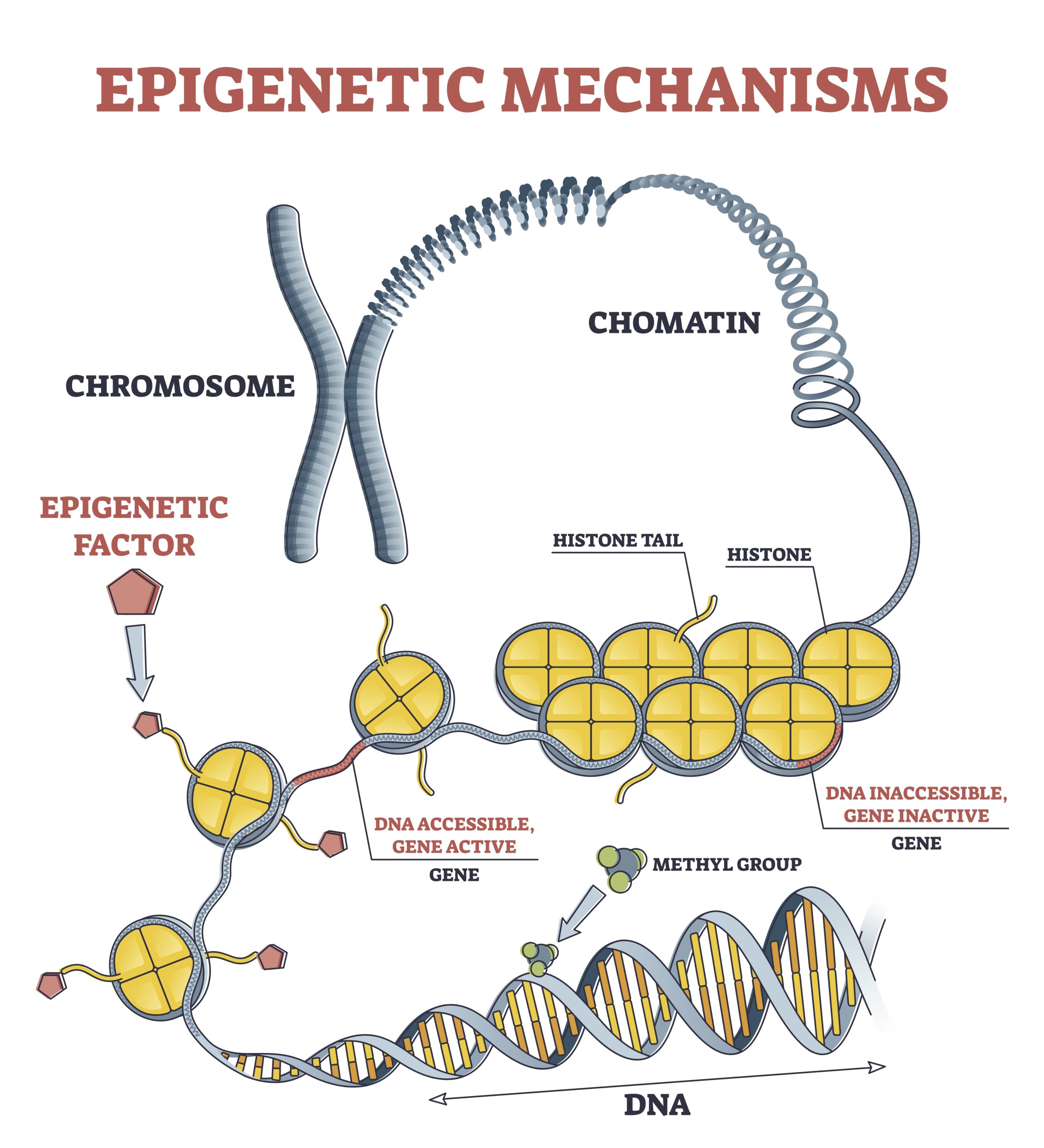

DNA contains our genetic code written in A, C, T, and G’s and is in a double helix structure. Discrimination based on this information is prohibited by GINA. But discrimination based on epigenetic molecules or factors (an example of which are methyl groups, pictured above) that bind to the double helix and to other parts of the chromosome (composed of chromatin), which contain tightly coiled DNA around proteins (proteins called histones), may not be covered by GINA. These epigenetic factors or molecules are interrelated with our DNA and can be used to infer information about our DNA, like whether a gene of interested in active or inactive, and other private information about our health and habits in the past as well as suggest risks for the future.

Credit: VectorMine/ Shutterstock.com

The Human Genome Project, which aimed to generate the first sequence of the human genome, was launched in October 1990 and largely completed by April 2003 (though 2022 marked the first time the difficult to reach areas of the genome were 100 percent sequenced). At the time of GINA’s passage, there was some suggestion that the environment around DNA could also play a role in the development and manifestation of inherited disease — though the field of epigenetics was nowhere near where it is today. With technological advances in DNA sequencing, advances in machine learning techniques and their novel application to biological data, and scientific discoveries shedding light on epigenetics over the last two decades, there is now previously unimaginable data available from someone’s epigenetics.

Direct-to-Consumer Epigenetic Tests Will Proliferate, Generating Sensitive Consumer Data

Unlike DNA, epigenetics changes throughout a person’s lifetime in response to environmental factors. It can be used to tell information not only about a person’s genetics and ancestry, but also their lifestyle, past behaviors, and experiences. Using a tissue sample like blood or a swab inside the cheek to look at the environment around a person’s DNA, scientists can infer with high accuracy whether a person is or was previously a cigarette smoker, likely past experiences of trauma, an estimate of a person’s age, risk for early mortality, ancestry, and more.

Models that make inferences based on epigenetics and age are already in use — especially when it comes to age and estimated rates of aging (at the molecular level, some people age at different rates than their chronological age in years). In 2016, a life insurance company, employing deceptive commercial promotion of the tech, began using a new epigenetic technology to assess people’s life expectancy. More at-home epigenetic testing companies are beginning to proliferate despite ethical concerns of potential for misuse, especially for the tests being developed for children. Some researchers and biotech startups believe future epigenetic technologies that can reprogram cells to a more youthful state will upend modern medicine, eliminating the need for the treatment of many age-related diseases. If this happens, people who opt out of epigenetic testing and surveillance may find themselves locked out of opportunities or forced to pay higher premiums for insurance or care.

Definitions in GINA Must be Updated to Protect Epigenetic Data

Congress took care to define “genetic information” broadly in GINA’s bill text, but over the years, the courts have been divided over how to interpret this definition, with some narrowing the interpretation and others keeping it broad. This division is now reflected in legislative debates in Congress over the breadth of the term. The ambiguity in GINA when it comes to epigenetic data stems from its definition of a “genetic test,” which it defined as “an analysis of human DNA, RNA, chromosomes, proteins, or metabolites, that detects genotypes, mutations, or chromosomal changes.”

This language was written at a time when genetic tests revealed “chromosomal changes” in the form of whole chromosome deletions or duplications — not the detailed data generated today. Moreover, GINA’s aim can be described as prohibiting employers and health insurers from making a predictive assessment of an individual’s propensity to develop a disease in the absence of symptoms, but not the emergence of a disease or disorder. Epigenetics, however, in reflecting both a person’s nature and nurture, sits somewhere between the two. Nowhere in GINA is the term epigenetics even used, reflecting an oversight that must be remedied. Any ambiguity in the language will be exploited and challenged by companies whose profits depend on discrimination.

Epigenetic Data Will Become Widespread in the U.S., Privacy Protections Must Catch Up

Americans have an ever-increasing appetite for gathering information about ourselves. This includes the expanded use of wearables to track sleep and activity, and the more than 26 million Americans willingly sharing their genetic information with companies like 23andMe to learn about unknown relatives, genetic mutations, and ancestry. Companies that offer ways to gather even more data about us continue to multiply. As we saw with the proliferation of at-home genetic testing companies, many consumers will be eager to get as much data as possible. But insurers, advertisers, and employers will be equally eager to get this information. This places increased pressure on Congress to ensure strong privacy protections around this genetic data, forward-thinking and oft-updated regulations in place dictating how such data can be used and by whom, and that companies using this data to discriminate be held accountable.

Amending GINA to deal with these problems will not solve all privacy issues likely to come up as the field of epigenetics continues to develop. A shift towards more knowledge of epigenetic data will require many necessary societal changes, not just in how patients interact with their health and insurance systems, but to what degree genetic and epigenetic data is obtained, stored, protected, and shared, including with law enforcement. Law enforcement access to genetic information is currently determined by states, and the Fourth Amendment and is not a subject of GINA. These concerns are especially relevant given that encryption algorithms developed for genetic information may not be suited for the protection of epigenetic information, and this should also be considered by policymakers.

The future of routine medical treatment and obtaining life and health insurance and employment may all soon touch on epigenetic tests. While Congress acted to ensure that discrimination based on genetic data is illegal, protections around discrimination based on epigenetic data, which can be even more sensitive, are unclear. Congress acted proactively when it passed GINA, and it should do so again by updating and clarifying the language of the law and revisiting it often as technological strides are made.

Date

Wednesday, May 24, 2023 - 10:45amFeatured image