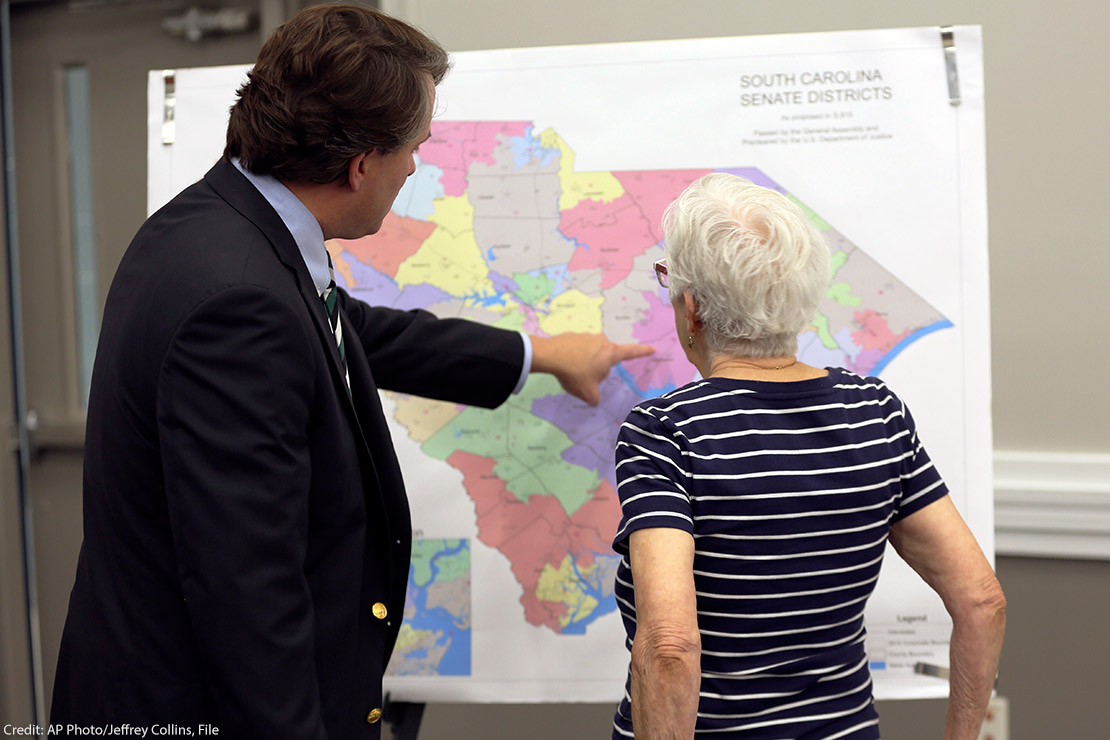

Racial discrimination exists in many forms. It can be as violent and overt as police brutality or as subtle as lines drawn on a voting map. In the latter case, the act may seem innocuous or technical, but the impact is significant.

Just look at what happened in January 2022. Ahead of the midterm elections, South Carolina’s majority-white and majority-Republican Legislature redrew Congressional District 1 (CD 1) to maintain political power. But it purposefully targeted Black communities to do so. Mapmakers unnecessarily moved thousands of Black voters out of the district in textbook racial sorting.

But the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment forbids the sorting of voters on the basis of their race.

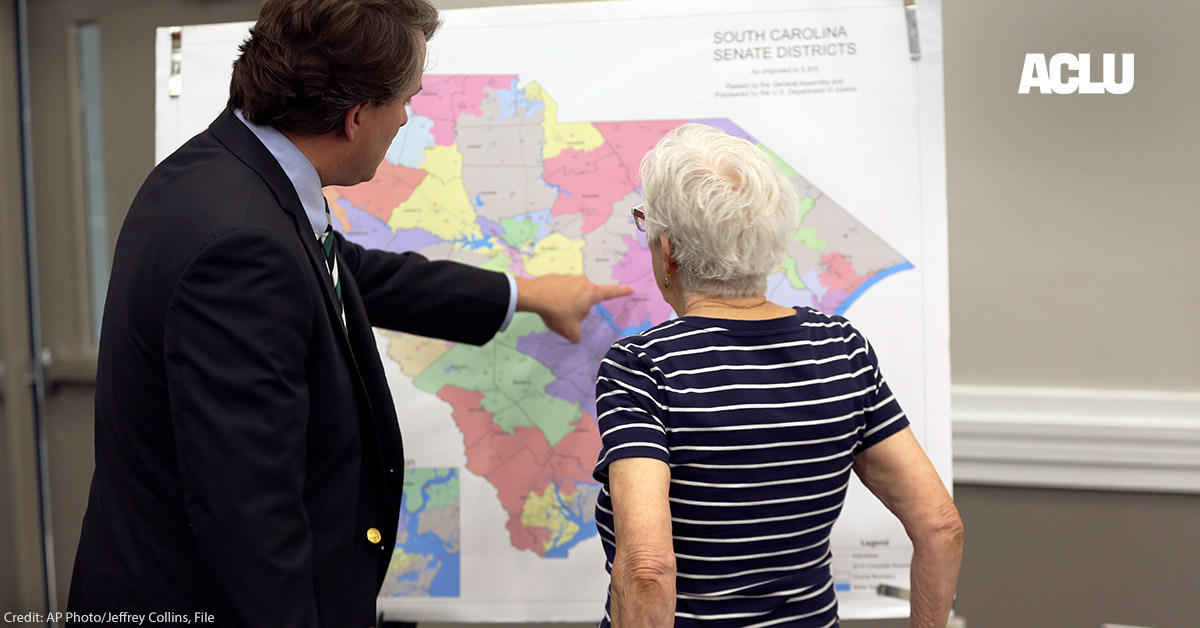

That’s what’s being argued in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP. The American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU of South Carolina, Legal Defense Fund (LDF), and Arnold & Porter challenged the map on behalf of the South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP and an individual voter, Taiwan Scott.

In January 2023, a unanimous federal three-judge court ruled that CD 1’s configuration in the 2022 map was unconstitutional because the Legislature sorted Black voters by race, and that therefore South Carolina would have to redraw it. The state appealed the ruling, however, and the Supreme Court is now set to hear oral argument on October 11.

Here’s a closer look at why this redistricting case is so important and what it could mean for Black communities in South Carolina — and across the country.

What is redistricting and why is it so important?

Redistricting is the process of redrawing the district maps on the basis of which public officials are elected. This process occurs every 10 years to account for new census data and population changes, because the Constitution requires that each district have roughly the same number of voters.

Redistricting can affect election outcomes from the federal to the local level. As a result, it can affect how communities are represented in government and how resources are distributed for health care, education, and infrastructure.

What is gerrymandering?

The redistricting process is vulnerable to abuse: it is an opportunity for legislators interested in protecting their seats to pick their preferred voters and to displace disfavored ones. A “gerrymander” refers to a district map that has been drawn to manipulate the outcome of elections. The term was coined in 1812, referring to a salamander-shaped district designed to favor Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry’s political party.

Today, districts are drawn using vast amounts of data, with increasingly sophisticated methods and software that heighten the ability of legislators to pick and choose between voters. This precision enhances the opportunity for gerrymandering.

South Carolina’s Legislature, for example, gerrymandered CD 1 by targeting and drawing Black communities out of the district, “exiling” them to adjacent districts — as the trial court found in the Alexander case.

Gerrymandering, by skewing the composition of a district, can prevent voters’ voices from being heard and unfairly distort election results.

How do redistricting and gerrymandering disproportionately affect Black communities?

Redistricting and gerrymandering affect all communities, but, in practice, they often have a disproportionate impact on communities of color. That’s because these practices are often employed to limit their ability to vote for representatives who can advocate for their needs and make their voices heard. When legislatures sort by race, as the court found happened in South Carolina, the legislatures also entrench the belief that representatives need only respond to members of a particular group.

In South Carolina’s CD 1, gerrymandering prevents voters from accessing representatives who could fight for economic development, affordable housing, healthcare, resources for historically Black colleges and universities, and broadband internet, among many other issues.

Why is South Carolina’s CD 1 district map considered unconstitutional?

South Carolina unlawfully assigned voters to congressional districts based on their race and intentionally discriminated against Black voters. It acted in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which forbids the sorting of voters on the basis of their race, absent a compelling interest such as satisfying an obligation under the Voting Rights Act. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments also forbid intentional racial discrimination.

In January 2023, a panel of three federal judges unanimously concluded that South Carolina’s congressional map is unconstitutional.

How is the ACLU working to fight discrimination in the redistricting process?

The ACLU works to ensure that redistricting takes place in a fair way that respects all voters and their communities.

In Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, the ACLU is advocating for the implementation of a fair and lawful CD 1 map in time for the 2024 election cycle.

What will happen when the Supreme Court hears this case?

The case is set to be heard at the Supreme Court on October 11. Because the lower court applied settled legal principles and concluded that the CD 1 map was unconstitutional based on extensive evidence, we are confident that the Supreme Court will do the same.

Black voters in CD 1 have already had to vote under an unconstitutional map once in the 2022 midterm elections. They shouldn’t have to endure that injustice in the upcoming 2024 elections, or ever again. We will fight until Black South Carolina voters have a lawful map that fairly represents them.

Date

Tuesday, October 10, 2023 - 1:45pmFeatured image