Last week, the National Policing Institute, in cooperation with the Department of Justice division on Community Oriented Policing Services, issued guidance to state and local law enforcement agencies on specialized units. NPI’s first recommendation is for law enforcement agencies to question whether they should create specialized units, and there’s an easy answer: no.

Specialized units vary but, as relevant here, they are sub-divisions of police departments tasked with enforcement related to specific conditions in an aggressive manner. The NPI guidance begins with a recognition that specialized units “are often subject to relatively limited supervision and afforded immense discretion when carrying out their duties.” This combination can lead to “tragic consequences.”

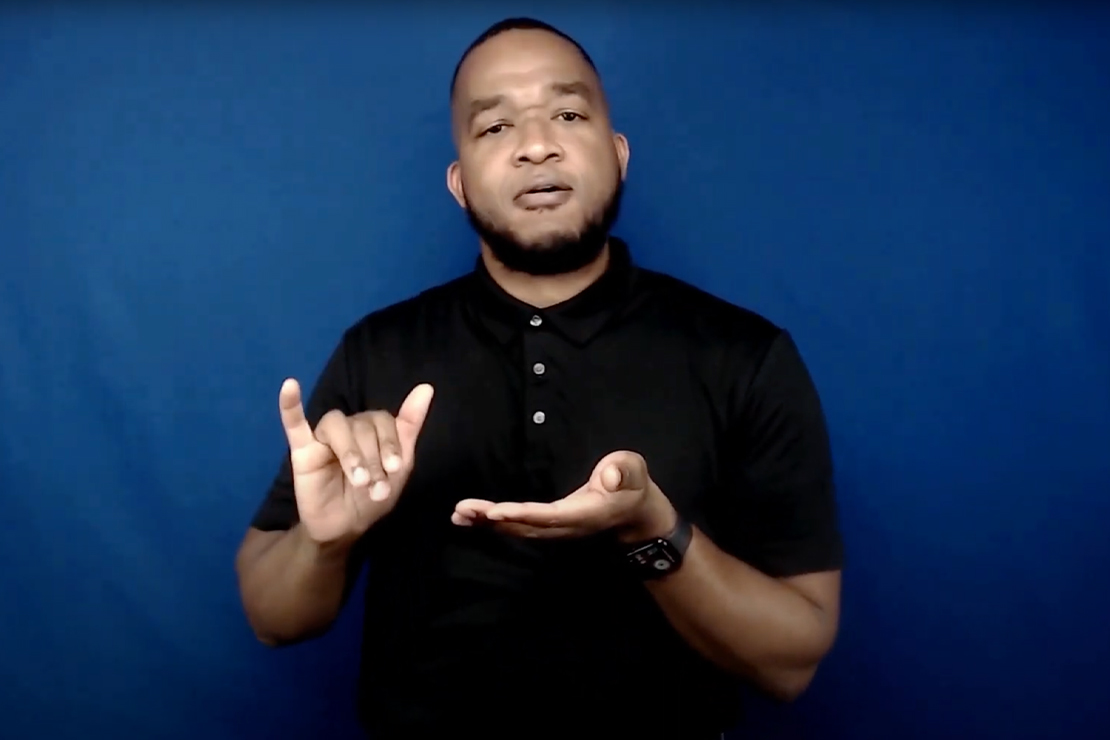

Indeed, the guidance was animated in part by the killing of Tyre Nichols in Memphis by officers from the Scorpion Unit — a specialized unit comprised of officers focused on crimes related to theft, gangs, and drugs. The Scorpion Unit stopped Nichols, a 29-year-old Black man, for a traffic infraction. They then pepper sprayed him and shot him with a stun gun despite his offering no apparent resistance. After yelling for help, Nichols ran toward his mother’s house. It wasn’t far from there that the officers — who had gone after him — beat him for several minutes while he was on the ground. He died days later from blunt force trauma to the head. Nichols’s family got the Scorpion Unit disbanded, with help from civil rights lawyer Ben Crump.

The Scorpion Unit was no aberration. In introductory remarks to its guidelines, NPI mentions the CRASH scandal in Los Angeles in the 1990s, during which a specialized unit tasked with addressing gang activity was found to be engaged in criminal conduct. The unit had repeatedly used excessive and at times lethal force without provocation. Another high-profile example is from New York City in 1999, when a specialized unit of the NYPD killed Amadou Diallo, a 23-year-old Black man. The unit — tasked with addressing gun violence — shot Diallo 41 times when he reached for his pocket to provide identification.

Disbanding these units does not necessarily end the misconduct. In response to community outcry over the Diallo killing, the NYPD dismantled the responsible unit and created a new one — the Anti-Crime Unit — that supposedly had better training and oversight. The ACU went on to be a primary driver of unlawful stops in the early 2000s and, more recently, was found disproportionately responsible for shootings. Following the George Floyd protests in 2020, the ACU was disbanded only to be reconstituted in 2023 — again, with allegedly better training and oversight. Just a few months after the new rollout, however, a federal monitor found ACU to be unlawfully stopping Black and Latine people.

How, then, should police departments and communities decide whether forming a specialized unit is worth the risk? NPI recommends that law enforcement should consider a series of critical questions before deciding to create or continue a specialized unit. That’s the right starting point. And it’s also good that NPI’s list of key considerations includes whether the affected community prefers non-law enforcement alternatives. Yet this question is only meaningful if communities are given real alternatives, and they rarely are.

Asking communities to choose between a specialized unit or nothing is a false choice, and alternatives might not be viable without additional investments. Police departments often have a heavily resourced infrastructure with round-the-clock staffing. As NPI points out, this sometimes makes police a default candidate for addressing problems they are not suited to solve. While creating alternatives might require more time and money, we must build solutions that reduce mismatched reliance on police. Otherwise, we’re not actually improving safety in the long run.

Notably, determining community preferences should be a thoughtful and deliberate process that reflects an understanding that communities are not monolithic. We emphasize the need to seek input from people who have experienced police misconduct through forums police do not attend, which NPI also recommends. People who have been subjected to unfair policing — directly or as witnesses — have important insight into its manifestations and harms, and this insight is critical to designing effective solutions. Police attendance at forums soliciting input from this population might undermine participation, given mistrust and fear that result from oppressive policing.

We’re skeptical of specialized units because of their history of violence and abuse — a problem that has shown to persist despite improvements in training and oversight. Their vast discretion and the realistic limits of internal accountability mechanisms inures specialized units with too much power, which has proven too much risk to impacted communities. NPI’s guidelines offer important suggestions for limiting the harms caused by specialized units, and these recommendations should be followed if specialized units are to continue. If we want to keep people safe from both crime and police violence, though, we need to build something better.

Date

Wednesday, January 17, 2024 - 11:30amFeatured image