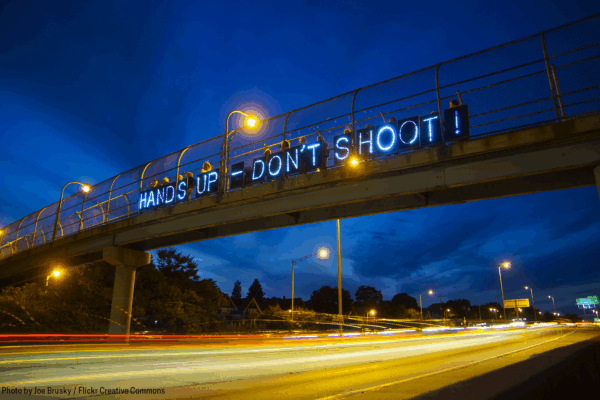

Four years after the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Americans are grappling with issues of race and disparity on the frankest terms since the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

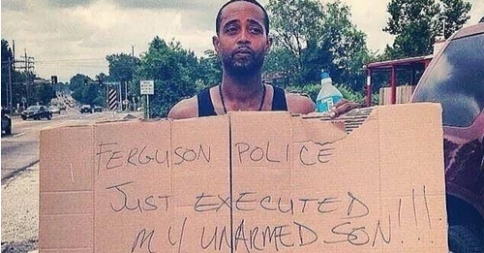

We all know the story by now: 18-year-old Michael Brown goes to a convenience store in Ferguson with a friend, he leaves and is stopped by white male police officers, is involved in an altercation, and ends up shot dead by one of those cops.

As a result, Brown became just one among many black boys and men who’ve had their lives brutally cut short at the hands of law enforcement officials. And in the immediate aftermath of the shooting, the way the predominately white local law enforcement agencies responded to the largely peaceful protests of the majority African-American community in Ferguson – with military tactics and a deliberate smear campaign of Brown – served as a clear reminder that race matters in American policing.

Michael Brown. Philando Castile. Walter Scott. Keith Lamont Scott. Eric Garner. Alton Sterling. Stephon Clark.

We know their names, and we know their faces. Many of us grimace and squirm at the implications of the killings of individuals who, according to our legal system, should be innocent until proven guilty, but are oftentimes found guilty based on assumption at first glance.

We know the numbers. 1 in 3 black boys born in this country will end up in prison, compared to 1 in 17 white boys. People of color are held in pretrial detention longer than white arrestees.

These issues are vestiges of a shrouded and complicated American history with race that can be difficult to grapple with. Overcoming the legacy is an ongoing struggle.

Awareness, or “wokeness,” of one’s conscious and unconscious biases is among the first steps to combat the issues of systemic racism that led to the death of Michael Brown and the many boys and men like him.

Dealing with the socioeconomic effects of the political subjugation of black people in America for three centuries, through the 1960s civil rights legislation meant to undo much of it, will take years and generations to rectify.

But, perhaps, a look at our criminal justice system and the way it punishes black men and women, and people of color for simply existing is a good place to start.

In Ferguson itself, the ACLU sought to address racism in the criminal justice system, responding with lawsuits demanding the police release documents to the public to make clear what happened in Mike Brown’s shooting, as well as a federal lawsuit against the local school district for policies that have shut African-Americans out of the political process. Here in Florida, the ACLU is pushing for criminal justice reforms at the legislative level to end overincarceration and reduce racial disparities in who is impacted by the system.

A half-century before Brown’s death in Ferguson, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered remarks in a St. Louis speech months before the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. King said, in part, “We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.”

When our society decides to see brown and black boys and men as youth, children, friends and neighbors as opposed to hoodlums, thugs, or threats, and black folks begin to feel wholly valued by society at-large, then maybe the dream of a “post-racial” America will finally come to pass.

This week, voters in St. Louis County unseated the prosecutor who oversaw the grand jury proceedings that resulted in the non-indictment of the officer who shot and killed Mike Brown. Real change is possible.

In Ferguson and across the country, we will continue to fight to advance equality in a nation that struggles with equality for all. Until then, the struggle for real equality continues.