Two years ago, Carolyn LaFeir was preparing for her son Carl Emerson King to come home from prison. Decades earlier he had been involved in a drug deal that went bad and he was wrongfully convicted of first degree murder even though he did not kill anyone and was not even present when the drug dealers were killed. After this grave miscarriage of justice was recognized by the very prosecutor who got him convicted, he was slated to be awarded clemency with the support of Gov. Rick Scott and Atty. Gen. Pam Bondi, who were then members of the Florida Board of Executive Clemency.

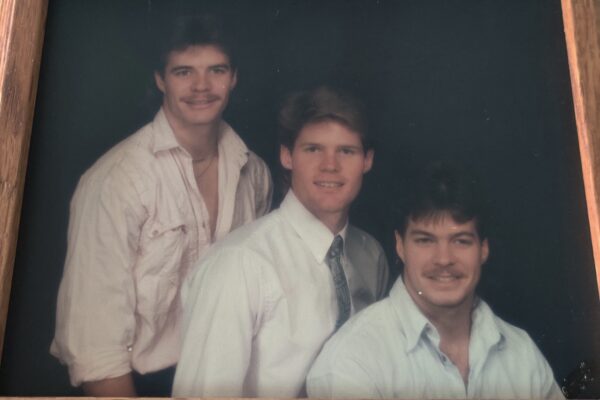

It had been 25 years since Carolyn had watched her 26-year-old son led to prison. He is now 51.

But Carl didn’t come home. His clemency hearing was postponed due to former president George H.W. Bush’s funeral, which both Scott and Bondi attended. By the time his postponed hearing arrived, there was a new governor and a new attorney general. They denied his request.

Now, Carolyn is one of many mothers living in fear that their child will die in prison. Carl wasn’t given the death penalty. Instead, he faces a potential death sentence by virtue of living in a Florida prison during a pandemic.

When people in Florida prisons started dying of COVID-19, the Florida Department of Corrections (FDOC) tried to hush it up. Only after accounts of the deaths leaked to the media did the state admit the fatalities. To date, the Department of Corrections has publicly reported that 18 people have died. These individuals – sons, daughters, mothers, fathers – had not been sentenced to death, but their presence in a Florida prison in the time of COVID-19 proved to be a death sentence due to the Department’s failure to protect those in its custody from COVID-19.

Moreover, it is clear that FDOC is underreporting the number of COVID-19 related deaths of people in their custody. On their website, they list only 18 individuals having died from COVID-19, but this number is misleading. The Department has chosen to narrowly define COVID-related deaths as including only those individuals who received a positive COVID-19 test prior to their death. Based on this, it appears that FDOC is not accounting for any COVID-related deaths where individuals had not yet received testing or were tested after they had died. This is particularly concerning, as less than 15 percent of the prison population has received testing.

Just this week, the state revealed that at least 3,035 people held in 57 facilities had been exposed to COVID 19 and were in medical quarantine or medical isolation. A total of 1,692 prisoners and 332 staff had already tested positive for the virus, but only a very small percentage of the 95,000 state prisoners had been tested.

We, as well as our partners, are pushing the State to free as many people from prisons and county jails as possible without jeopardizing public safety. This effort is revealing just how many people are being kept behind bars in Florida who don’t need to be there, and just how expensive it is for taxpayers. The state corrections budget alone is $2.8 billion this year and that doesn’t count hundreds of millions of dollars more spent by counties to house some 50,000 people in their jails at any one time. If that money had gone to hospitals rather than prisons, Florida would be much better off now.

That said, already hundreds of individuals have been freed from jail in Florida since the pandemic descended. Many were behind bars accused of misdemeanors – possession of small amounts of drugs, petty theft, trespassing, public intoxication, etc. They had not been convicted of anything; they simply did not have the money they needed to make bail and were sitting in jail waiting to appear before a judge. Should the lives of individuals who cannot afford bail be put at risk in county jails where social distancing is all but impossible? Obviously not, which is why some are being released, but so many more need to be freed.

In Florida prisons, the crisis is no less urgent. According to FDOC data, as of April 2020, 4,772 people in our prisons are 65 years old or older, making them particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. In fact, some 28 percent of all incarcerated individuals in state prisons are 50 and over. Because people in custody tend to be in worse health than the average population, they are officially considered “aging” by state statute at age 50 -- and more vulnerable to the virus.

Some 7,000 of those over 50 are in prison for non-violent crimes – burglary, theft, forgery, fraud, drug offenses. Some of those individuals have been in prison for many years, serving excessively long and extremely expensive sentences provoked by Florida’s draconian sentencing laws. Despite years of bipartisan support for meaningful reform to reduce our ballooning prison population, Florida’s leaders continue to block sensible and humane reforms every year.

And now, many, like Carl King, are facing potential de facto death sentences due to COVID-19. Recidivism rates among senior citizens released from prison are miniscule. Letting them die of the coronavirus behind bars would be a travesty.

Like Carolyn, many mothers, fathers, and children have not been allowed to visit their loved one in prison since the pandemic began. They live in fear that the virus will mean they will never be able to see their loved one alive again.

Carolyn is 70 years old now, and her son is 51. They are both at increased risk of COVID-19 complications. Carolyn can protect herself, but Carl cannot. Carl has been in wrongfully in prison for 25 years on a first degree murder charge, a crime that he did not commit. His case demonstrates how tragic the criminal justice system can be in Florida. When it comes to addressing serious crimes in Florida, one size does not fit all.

Did Carl commit first degree murder? No. Not even the prosecutor who convicted him, former Hillsborough County Assistant State Attorney Nicholas Cox, believes he did.

Carl is in prison because a 1994 attempt to steal 100 pounds of marijuana went bad and two drug dealers ended up dead. He was not involved in killing these men. He wasn’t even present for their murder. He’s in prison today because when the prosecutor, Cox, offered a maximum 20-year sentence on second degree murder charges, the public defender representing King foolishly turned it down without telling her client.

Attorneys are required to tell their clients of such offers. Carl didn’t get a chance to even consider this, and ended up convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life. The public defender was later disbarred for incompetence. If she had given Carl the opportunity to accept the plea offer, he could have gone home, as early as 2012.

But the vagaries of the system don’t stop there. Carl has been a model prisoner, without a disciplinary report in 13 years, according to FDOC records. The past six years he has served as a chaplain’s assistant at DeSoto Correctional Institute in Arcadia.

Between this sterling record and the testimony of his prosecutor, his clemency application should have been approved. “Mr. Cox told us it was pretty much a done deal,” says Carolyn.

But with the last-minute postponement, Scott and Bondi weren’t able to rule and the new Clemency Board, headed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, was not swayed by the prosecutor’s testimony or Carl’s sterling record. Cox told the board that others who played a greater role in the killings were already free, while Carl was still locked up.Should a man be in prison when even the prosecutor who convicted him believes he shouldn’t be? For the family, it is grueling.

“We came so close two years ago,” says his mother.

Now, Carolyn has to worry that her son will be exposed to COVID-19.

“He works in the chapel, so he is typically in contact with many guards and prisoners on a daily basis,” she says. “His health is not great and now I have to worry he will come in contact with this deadly virus.”

Carolyn is not the only mother worried that she’ll never get to see her incarcerated child again. Unfortunately, there are thousands of Carl Kings unjustly locked up in Florida’s prisons for decades on charges for offenses they did not commit or for excessive sentences that have no relation to the offense committed or for lengthy sentences that have since been abolished.

King needs justice now and should be released to his family. King’s case is yet another reason Floridians should take a careful look at who is being kept behind bars, not just during the pandemic but in the years to come.