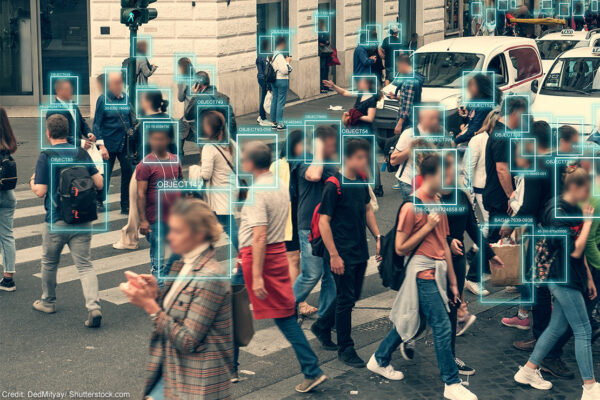

Secretly, and without consent, a company called Clearview AI has captured billions of faceprints from people’s online photos, amassing what it claims to be the world’s largest face recognition database. Much like our fingerprints and DNA profiles, our faceprints rely on permanent, unique facts about our bodies — like the distance between our eyes and noses or the shape of our cheekbones — to identify us.

Using our faceprints, Clearview offers its customers the ability to secretly target and identify any of us, and then to track us — whether we’re going to a protest, a religious service, a doctor, or all of the above — and even to reach back in time to find us in old selfies, school and college photos, and videos. In other words, it might end privacy as we know it. It also threatens our security and puts us at greater risk of identity theft by maintaining a massive biometric database, akin to a secret warehouse of housekeys.

Clearview’s nonconsensual capture of our faceprints is dangerous. It is also illegal in at least one state.

In May of last year, we sued Clearview for violating Illinois’ Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA), a state law that prohibits capturing individuals’ biometric identifiers, like face and fingerprints, without notice and consent. We represent a group of organizations whose members and service recipients stand to suffer particularly acute harms from nonconsensual faceprinting and surveillance: survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault, undocumented immigrants, current and former sex workers, and individuals who regularly exercise their constitutional rights to protest and access reproductive health care services.

Notwithstanding these harms, Clearview asked the court to dismiss our case, arguing, in part, that the company has a First Amendment right to capture our faceprints without our consent.

As advocates for both free speech and privacy, we take this objection seriously — and we strongly disagree. As we explained to the court previously and again this week, Clearview’s view is at odds with long-established First Amendment doctrine, and could spell the end of privacy and information security laws if accepted.

Clearview argues that, to create its face recognition product, it gathers publicly-available photographs from across the internet and then uses them to run a search engine that simply expresses Clearview’s opinion about who appears to be in the photos. Clearview claims that, like a search engine, it has a First Amendment right to disseminate information that is already available online.

But our lawsuit doesn’t challenge — and BIPA doesn’t prohibit — Clearview’s gathering or republishing photographs from across the internet, or expressing its views about who appears in those photos. Clearview is free to discuss or disseminate photographs it finds online. What it can’t do under Illinois law is capture people’s faceprints from those photographs without notice and consent. That is a distinct action, which can cause grave harms.

Accepting Clearview’s argument to the contrary would mean agreeing that collecting fingerprints from public places, generating DNA profiles from skin cells shed in public, or deciphering a private password from asterisks shown on a public login screen are all fully protected speech. And it would depart from decades of judicial precedent permitting laws banning wiretapping, stealing documents, or breaking into a home — all acts that become legal if done with consent — even when that conduct might generate or capture newsworthy information. In other words, the fact that a burglar intends to publish documents they steal doesn’t mean the burglary is protected by the First Amendment. Likewise, the fact that Clearview intends to disseminate people’s photos after capturing faceprints from them doesn’t mean the company has a constitutional right to capture the faceprints without consent.

At the same time, BIPA does have an incidental effect on the speech Clearview seeks to engage in after capturing a faceprint, and so the law is subject to some First Amendment scrutiny. In United States v. O’Brien, the Supreme Court explained that regulations of conduct that have an incidental effect on speech are subject to so-called “intermediate scrutiny.” That means that the First Amendment is satisfied as long as (1) the government has the power to enact the regulation in the first place, and (2) the regulation furthers an important government interest that (3) isn’t related to suppressing free expression, and (4) burdens speech no more than it necessary to further the government’s interest.

BIPA — and its application to Clearview in our lawsuit — satisfies that test.

First, Illinois has the power to pass a law like BIPA, which is designed to protect its residents against irreparable privacy harms and identity theft.

Second, BIPA’s notice-and-consent requirement furthers the state’s substantial interests in privacy and security. Our faceprints can be used to track us across physical locations, photographs, and videos, painting a complete picture of our lives and associations. This threat of surveillance also chills our speech. And, because biometric identifiers are often used to enable access to secure locations and information — like the face recognition feature on our phones or the fingerprint scan to enter our offices — the capture of our faceprints without our notice and consent poses security risks.

These dangers aren’t hypothetical. In recent months, government actors have relied on faceprint technology to identify and track protesters in cities and on college campuses, and such technology has resulted in at least two false arrests in Michigan and at least one in New Jersey. Clearview AI has contemplated providing its technology to a “pro-white” Republican candidate to conduct “extreme opposition research,” and it has given access to more than 200 companies, as well as celebrities and wealthy businesspeople, to use as they would like, including to identify who their children are dating. Recently, it entered into a contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. And, in the last year, it suffered a data breach (though thankfully not of its faceprint database).

Third, Illinois’ interest in BIPA’s notice-and-consent requirement is not about silencing or limiting speech. BIPA does not prevent anyone, including Clearview, from discussing the topic of identity or from expressing an opinion about who appears to be in a photograph, regardless of what that opinion may be. Indeed, even if Clearview didn’t speak at all, and simply captured faceprints that it kept in a massive, insecure database, it would violate BIPA. BIPA is not a regulation of speech.

Finally, BIPA’s notice-and-consent requirement is sufficiently tailored to Illinois’ substantial interests in protecting privacy, security, and speech. The problem BIPA seeks to solve is individuals’ lack of knowledge about and control over the capture of their biometric identifiers — and requiring notice and consent perfectly solves it. At the same time, the law doesn’t restrict more speech than necessary because it doesn’t ban the use of faceprints; it simply requires consent first.

If Clearview’s position prevails, states will be powerless to enact protections against violations of privacy that involve data. But that is a dangerous misreading of the First Amendment. Reasonable notice-and-consent laws governing conduct, like BIPA, simply do not violate the First Amendment.