Investing in community-based treatment instead of locking people up for the psychological wounds of war would honor veterans.

Shawn Jensen was 17 years old and escaping an abusive foster family when he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1966. One year later, Shawn was sent to Vietnam, where he faced combat and was wounded twice. By December 1967, Shawn’s superior infantry skills set him apart and he was trained as a member of the elite Reconnaissance Battalion, where he and a team of seven to eight men were sent on multiple long-range patrols deep into the jungles of Southeast Asia to gather intelligence, often without any reinforcements. Shawn again faced combat, danger, and death, and was repeatedly exposed to Agent Orange. For his service in Vietnam, he earned multiple military awards, including a Purple Heart.

Show Up for Civil Liberties: Donate Now.

From free speech to reproductive freedom to immigrants' rights, the ACLU has shown up for over 100 years to protect civil liberties and civil rights for all — and we won't stop now. Donate today to help fund critical litigation, advocacy, and grassroots efforts.

Shawn returned to the United States after 13 months of combat and recon, met and married his wife, Rhonda, and attempted to rebuild his life after the war. After Shawn returned, he began to have flashbacks to times of combat with enemy soldiers as well as experiencing many other symptoms of what we now know as PTSD.

The damage to the bodies and minds of people like Shawn who fight our nation’s wars must be acknowledged and recognized by the same political leaders who send them abroad.

Shawn recognized that something was wrong, and he and Rhonda were trying to get him help for what was then known as “shell shock.” Shawn describes his flashbacks as being “totally removed from everyone, anything, in an instant, completely immersed, with no ambiguity, fully within a particular combat situation.” Shawn’s invisible wounds continued to manifest, and in March 1973, while walking alone through the Arizona desert with his guns, he suddenly saw a figure rise up behind a tree and flashed back to Vietnam. Tragically, during this flashback he ended up killing a teenage couple who were out enjoying the Arizona desert. Just over a month prior to their deaths, Rhonda had taken Shawn to the local ER because of his mental health concerns. The ER discharged him describing “acute onset flashbacks to Vietnam, recommend psychiatric treatment at VA hospital …” He was awaiting this treatment when he killed the two people who were just a few years younger than he was.

Shawn was given two life sentences for killing the couple and has been locked up in Arizona’s prisons since 1973. In his first nine years of incarceration, he sought out cognitive behavioral therapy, and obtained two bachelors’ degrees, and Shawn and Rhonda celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary last year.

Shawn Jensen in his Marine Corps military police uniform in 1969.

Image courtesy of Rhonda Jensen

The ACLU National Prison Project first met Shawn in 2011, when he and Rhonda were trying desperately to get him treatment for the prostate cancer that doctors think was most likely caused by his exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam. Shawn became a lead named plaintiff in Jensen v. Shinn, our decade-long lawsuit to ensure that the nearly 30,000 adults and children in Arizona’s prisons receive the basic health care and conditions of confinement that they are entitled to under the Constitution and the law. Even after taking on this high-profile role, he struggled to receive care for a recurrence of prostate cancer.

Shawn’s experience after his military service is all too common. More than 180,000 veterans are incarcerated in the country’s jails and prison, according to the most recent available data, which is a decade old. (Only slightly more recent data from 2016 accounts for almost 110,000 veterans in federal and state prison custody.) The failure to keep up-to-date records on the number of incarcerated veterans is just another indication of how little care our government shows for people after their military service.

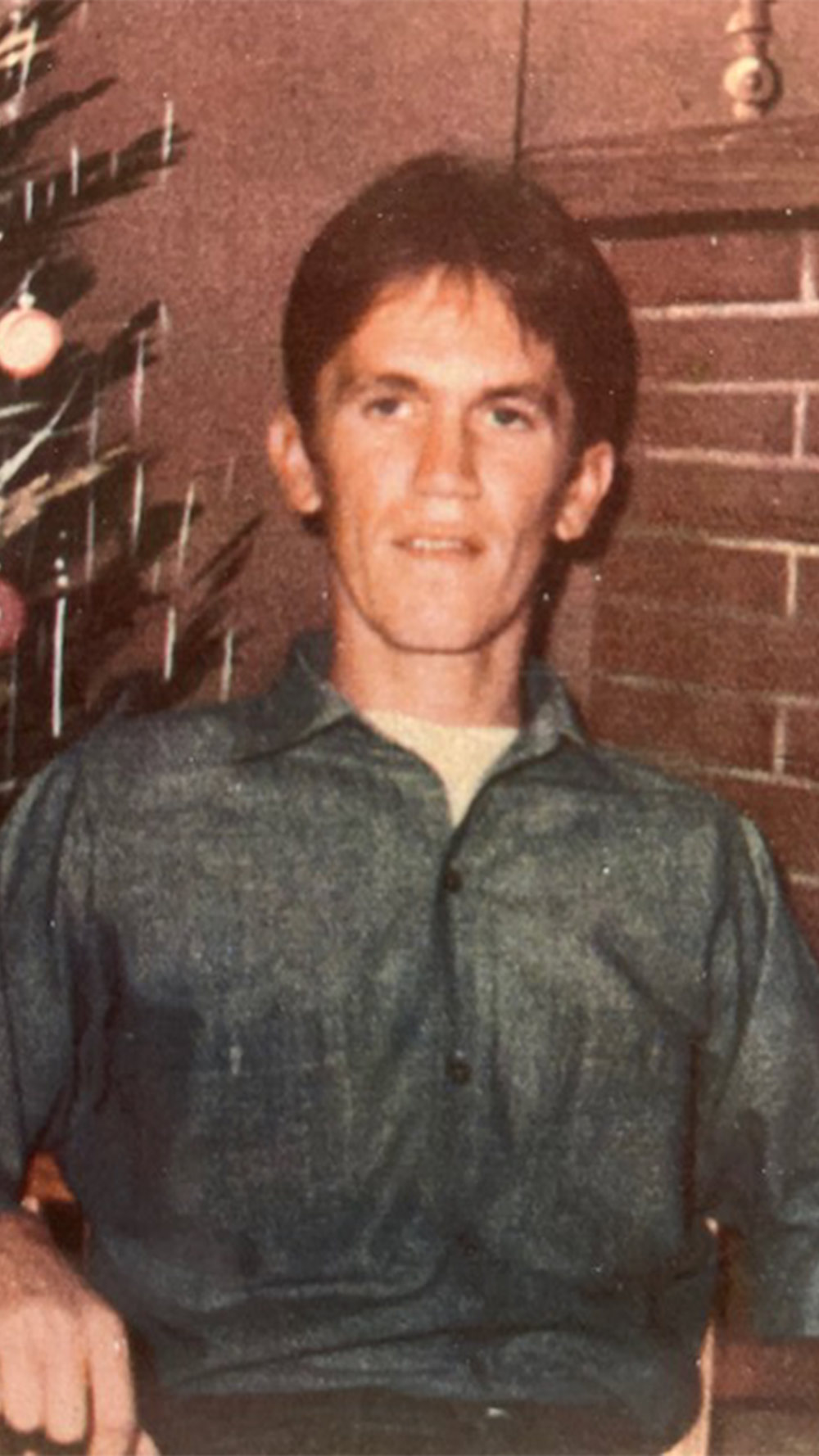

Shawn Jensen’s first Christmas in an Arizona prison when he was 24 years old (1973).

Image courtesy of Rhonda Jensen

For many incarcerated veterans, involvement in the criminal legal system is a direct result of psychological complications that arose from their service. It was not until 1980, years after Shawn experienced his first flashback, that the psychiatric community formally recognized PTSD. The Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that 15 percent of Vietnam War veterans experience PTSD, and 11 to 20 percent of veterans of the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan experience PTSD.

Over the years, research and science have allowed us to gain a better understanding of PTSD, its impact, and manifestations. We know now that PTSD can result from a traumatic event such as combat. PTSD can be triggered suddenly and can present in a variety of ways, and veterans with PTSD are about 60 percent more likely to be incarcerated than those without it. People with PTSD are also more likely have a substance use disorder, which can also lead to incarceration. In fact, almost one third of America’s war veterans have been arrested or booked into jail — nearly double the rate among civilians.

If, as a nation, we want to honor their service, we should invest in providing community-based treatment to help them heal after their military service, instead of deepening their wounds by incarcerating them.

There is still a lot to learn about why veterans are overrepresented in prisons and jails. Unlike in 1969, we now know that trauma-informed care, cognitive behavioral therapy, and support systems make a difference. Shawn experienced firsthand the power of working with another Vietnam veteran as a therapist, which allowed for a deeper understanding of his experience. Better access to VA facilities and education about mental health resources are a way to overcome barriers to care. Recovery meetings designed for veterans and active duty service members are another option, now offered virtually. Community-based treatment works for veterans, as evidenced by a decline in arrests, and yields positive outcomes, including increased productivity, fewer suicides, and lower incarceration rates.

The damage to the bodies and minds of people like Shawn who fight our nation’s wars must be acknowledged and recognized by the same political leaders who send them abroad. If, as a nation, we want to honor their service, we should invest in providing community-based treatment to help them heal after their military service, instead of deepening their wounds by incarcerating them. This Veterans’ Day, we recognize the almost 10 percent of our nation’s incarcerated people who once wore our country’s uniform and fought in our wars, and continue to advocate for the care and support they need.