Reform of the 1033 program, which arms local police with military equipment and weapons, is not enough.

The federal government arms local police forces in the United States with weapons of war. A program called “1033,” for the section of the act that created it, allows the Department of Defense to give state, local, and federal law enforcement agencies military hardware. Since its inception in 1996, nearly 10,000 jurisdictions have received more than $7 billion of equipment. This includes combat vehicles, rifles, military helmets, and misleadingly named “non-” or less-lethal weapons, some of which have featured in police raids and police violence against protesters, including recent protests for racial justice.

The ACLU helped place police militarization in the broader landscape of police violence with our 2014 groundbreaking report, “War Comes Home.” That report — released just months before police killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri — highlighted the ways that militarized police act aggressively and violently, target Black and Brown communities, and kill Americans at an alarming tempo. Our report proposed ways to address the militarization of police and recommended that the federal government limit the type of military equipment granted to law enforcement agencies, make data about the program publicly available, and significantly increase oversight over the 1033 program.

As police mounted heavily armed and sometimes violent responses to protestors in Ferguson and elsewhere, President Obama signed an executive order (E.O. 13688) in 2015 that implemented some of the ACLU’s central reforms — establishing oversight procedures for some classes of controlled equipment, banning a few categories of weapons entirely, and mandating that data about the program be made public. Donald Trump ran for office promising to rescind Obama’s 1033 restrictions. In 2017, shortly after encouraging police brutality in a speech to police officers on Long Island, Trump made good on his promise and rescinded the executive order.

President Joe Biden and Congress now face a decision about what to do with the 1033 program: should they re-reform it, or put a stop to transfers of military equipment to local police departments?

Our analysis of the 1033 program and the effects of the Obama reforms leads us to the conclusion that the 1033 program should be abolished. The quantity of military transfers to local police departments has decreased over time following the slowing demobilization from war, but the Obama-era reforms have done little to keep dangerous military equipment off of America’s streets. And contrary to the claims of its supporters, 1033 does nothing to make communities or officers safer.

Doing away with 1033 requires an act of Congress. Until Congress can pass the necessary legislation, President Biden should place a moratorium on transfers of military equipment under the auspices of 1033.

At War at Home and Abroad

The origins of 1033 lie in America’s “forever wars” on drugs, crime, and terror. In 1989, Congress gave the Pentagon temporary authority to give equipment that was no longer being used by the military to local police and sheriff’s departments. Armored vehicles, planes, rifles, scopes, grenades, bayonets — nearly everything was on the table, so long as the military “deemed [it] suitable … in counter-drug activities.”

In 1996, Congress made the Pentagon’s temporary authority to give weapons of war to local law enforcement agencies permanent and expanded its purview to “counterterrorism” as well, creating 1033 as we know it. The wars on drugs, crime, and terror are responsible for some of the most egregious violations of civil liberties, civil rights, and human rights of the past quarter century: mass incarceration, police killings, the forty-fifth president’s “Muslim ban,” in the U.S., as well as systematic torture, drone strikes, extraordinary renditions, and extralegal killings abroad. Local police forces armed with weapons of war — and still targeting Black and Brown Americans — is yet another inheritance.

Phillip Jones/National Guard Photo: Decommissioned military equipment is strategically dropped off the coast of South Carolina, where it will become one of many artificial reefs made of retired weapons of war. The world’s largest artificial reefs are built of retired U.S. military equipment.

Giving military equipment to local police departments was a significant break from established practice. For most of U.S. history, the policymakers who managed demobilization from war prioritized economic considerations. Their main task was to repurpose the tools of war and redirect the labor of returning troops to serve productive industry.

With the important caveats that policymakers intentionally excluded Black, Brown, and LGBTQ Americans from the economic gains of demobilization and treated women as second-class citizens, these efforts were profoundly successful. Americans built many industries — including technology, aerospace, fishing, shipping, and many others — with the factories, planes, and technologies that helped the U.S. win the Second World War. Equipment that served no useful economic purpose was typically stored or destroyed, often by transforming it into artificial reefs that rehabilitated local marine ecologies.

A Free-for-All: The 1033 Program Before 2015 Reforms

Massive demobilizations abroad in the late aughts and early 2010s brought 1033 transfers to new levels. Of the more than $7 billion worth of equipment that has been transferred to state and local law enforcement through 1033, more than half has been transferred in the last decade. Since 2011, transfers from the U.S. military to local law enforcement have averaged $390 million a year, and have been distributed to more than 6,500 local or state agencies in all 50 states and several U.S. territories.

Putting full battalions of equipment under the program’s purview challenged a system that lacked oversight and accountability. Though there were some hoops to jump through — governors in each state appointed coordinators to facilitate requests for equipment — the 1033 program in the early 2010s is best described as a free-for-all. Law enforcement agencies applied to receive military equipment and the Department of Defense distributed everything from coffee makers to rifles, combat vehicles, batons, and bayonets on a first-come-first-served basis.

Southlake, Texas Department of Public Safety Photo: Children pose with a mine-resistant ambush protected vehicle in Southlake, Texas acquired through 1033. After this photo was taken, Southlake officers restrained children as part of “handcuffing lessons.”

Though unprecedented government investment in police and sheriff departments had already facilitated aggressive and violent tactics, the influx of military gear from 1033 made a bad situation worse. Police used classes of weaponry distributed through the 1033 program in the 2011 crackdown against Occupy Wall Street protestors and in countless SWAT raids that left dozens of Americans dead. Law enforcement used an MRAP obtained through 1033 against people protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, where they also used tear gas, a water cannon, rubber bullets, pepper spray, and concussion grenades.

From 2011 to 2014 alone, the military distributed more than 29,000 military-grade rifles to 18,000 law enforcement agencies. Police militarization penetrated a number of aspects of American life — even law enforcement attached to K-12 public schools participated in 1033. The violent repression of the Ferguson protests in 2014 emphasized the severity of a long, troubling pattern of militarization. Something had to change.

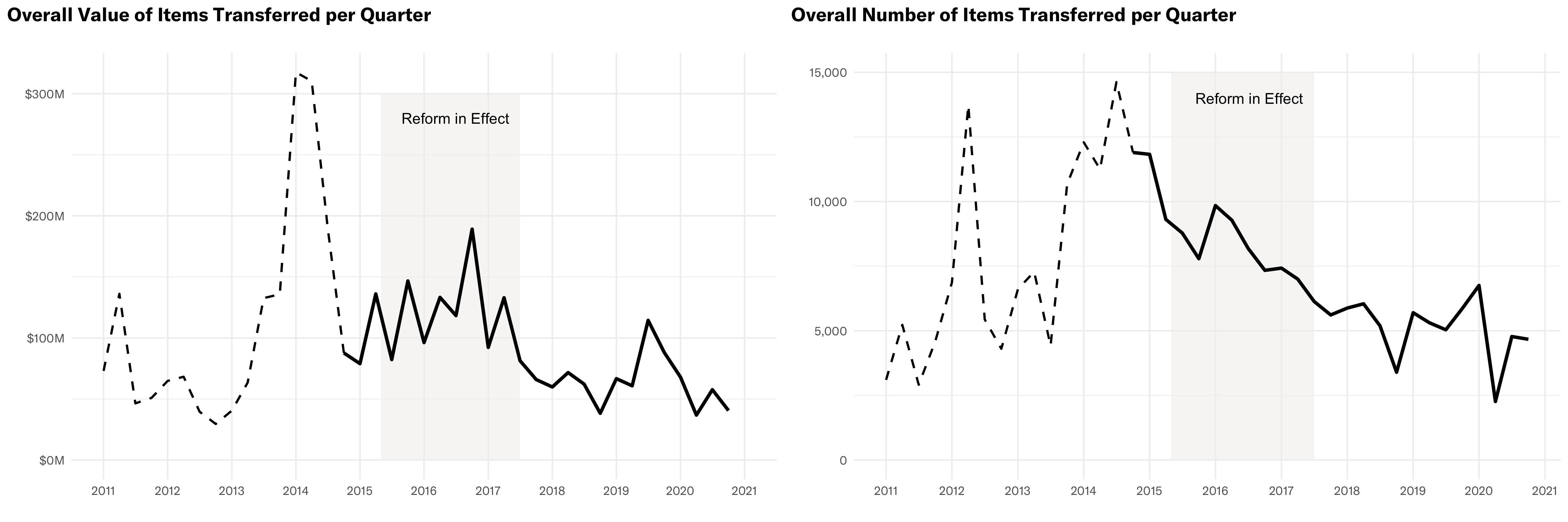

Transfers Before and After 2015 Reforms (E.O. 13688)

The total dollar value of new 1033 transfers per quarter (left) and the total number of individual items transferred through 1033 per quarter (right).

*An important methodological note is that data collection before 2014 was imperfect and pre-2014 figures should be understood as underestimates of equipment transfers. For a description of our data sources and methodology, see “How We Analyzed 1033” below

The 2015 Executive Order 13688 forbade the Department of Defense from transferring to law enforcement agencies some highly militarized equipment — for example, tracked and armored personnel carriers, grenade launchers, and bayonets — recalled some equipment that was already in circulation, and implemented new forms of oversight for the transfer of other items. The order also required that law enforcement agencies submit paperwork attesting to their need for the equipment, satisfaction of training requirements, approval from relevant civilian governing bodies, and compliance with civil rights law in order to receive military equipment. Finally, the order increased oversight of military transfers by establishing a supervisory body and requiring that data about transfers be tracked and made publicly available.

Close examination of E.O. 13688 reveals that its provisions were too narrow in scope to prevent the transfer of more than 100,000 items of controlled military equipment totalling more than $576,000,000 between the date the reforms were fully implemented on Oct. 1, 2015 and their repeal in August 2017. Very little equipment was actually banned by the E.O., and even the equipment that the E.O. specifically restricted does not appear to have decreased substantially, in large part because law enforcement agencies easily circumvented new oversight protocols.

Banned Items

The categories of banned equipment were narrowly tailored to comprise a small fraction of controlled equipment — less than half a percent of all controlled equipment in circulation a month before the ban went into effect. As a result, many dangerous items escaped the ban.

For example, the executive order banned and recalled vehicles that were tracked, armored, and manned, but left untouched vehicles that did not have all three qualities: tracked unmanned vehicles, armored trucks and tractors, some mine resistant vehicles, and a number of other combat, assault, or tactical vehicles. Out of at least 1,300 militarized vehicles in circulation at the time of Obama’s executive order, only 126 vehicles were recalled. These were quickly replaced, as almost 400 new military vehicles were transferred to local police during the period of the executive order.

The executive order also forbade the military from transferring some equipment that does not seem to have been part of the 1033 program in the first place. Firearms over .50 caliber and weaponized aircraft, for instance, were included in the list of 1033 equipment banned by Obama’s order, but no such equipment was in circulation at the time or has been transferred since.

Especially concerning is the fact that some banned equipment was not recalled or continued to be transferred to law enforcement organizations during the period that the executive order was in effect. Hundreds of camouflage uniforms escaped recall and 382 bayonets were transferred during the ban. The number of items banned by E.O. 13688 was tiny; the number of banned items that were appropriately recalled is even smaller. By quantity of individual items, the total number of recalled items represented less than a tenth of one percent of all 1033 equipment in circulation at the time.

City of Yukon, Okla. Photo: Police snipers at a 2018 training inside Oklahoma State University’s Boone Pickens Stadium. Rifles, scopes, and helmets are transferred to local police departments through the Pentagon’s 1033 program. Obama’s executive order did not halt the flow of these items to state and local law enforcement.

Restrictions and Oversight

In addition to banning a small number of items, E.O. 13688 also implemented restrictions on the transfer of others, requiring that law enforcement agencies demonstrate need, comply with civil rights law, and train officers appropriately. In most cases, these requirements simply amounted to paperwork to be filled out.

The Law Enforcement Supply Office, which runs the 1033 program, publishes quarterly updates of pending or cancelled transfers (in addition to the aforementioned inventory updates), which includes the justification for requested items. A review of those data reveal that law enforcement agencies tend to repeat the same vague justifications of “need.” For militarized vehicles, for instance, common justifications include “TO BE USED FOR ACTIVE SHOOTERS,” “FOR HIGH RISK OPERATIONS,” “HIGH RISK WARRANTS,” and “COUNTER DRUG.” There is little reckoning with whether these events are likely, and armored vehicles have often been transferred to tiny, rural towns. During the period of the reforms, sheriffs serving counties with populations of less than 5,000 people received night vision gear, sniper tools, an LRAD, and numerous military trucks. And 31 MRAPs or other highly militarized vehicles have been distributed to sheriffs serving counties of less than 10,000.

“Even the most highly publicized moments of police brutality seem to have had no effect on a law enforcement agency’s receipt of military equipment.”

Like the requirement to demonstrate need, the civil rights provision of the executive order amounted to a requirement that law enforcement agencies attest to their own compliance with civil rights law; whether any agencies were ever denied transfers because of civil rights abuses is unclear. In fact, even the most highly publicized moments of police brutality seem to have had no effect on a law enforcement agency’s receipt of military equipment. For example, Baton Rouge police received a helicopter mere months after the 2016 police killing of Alton Sterling, and NYPD received two mine-resistant vehicles just a couple of years after the 2014 police killings of Akai Gurley and Eric Garner.

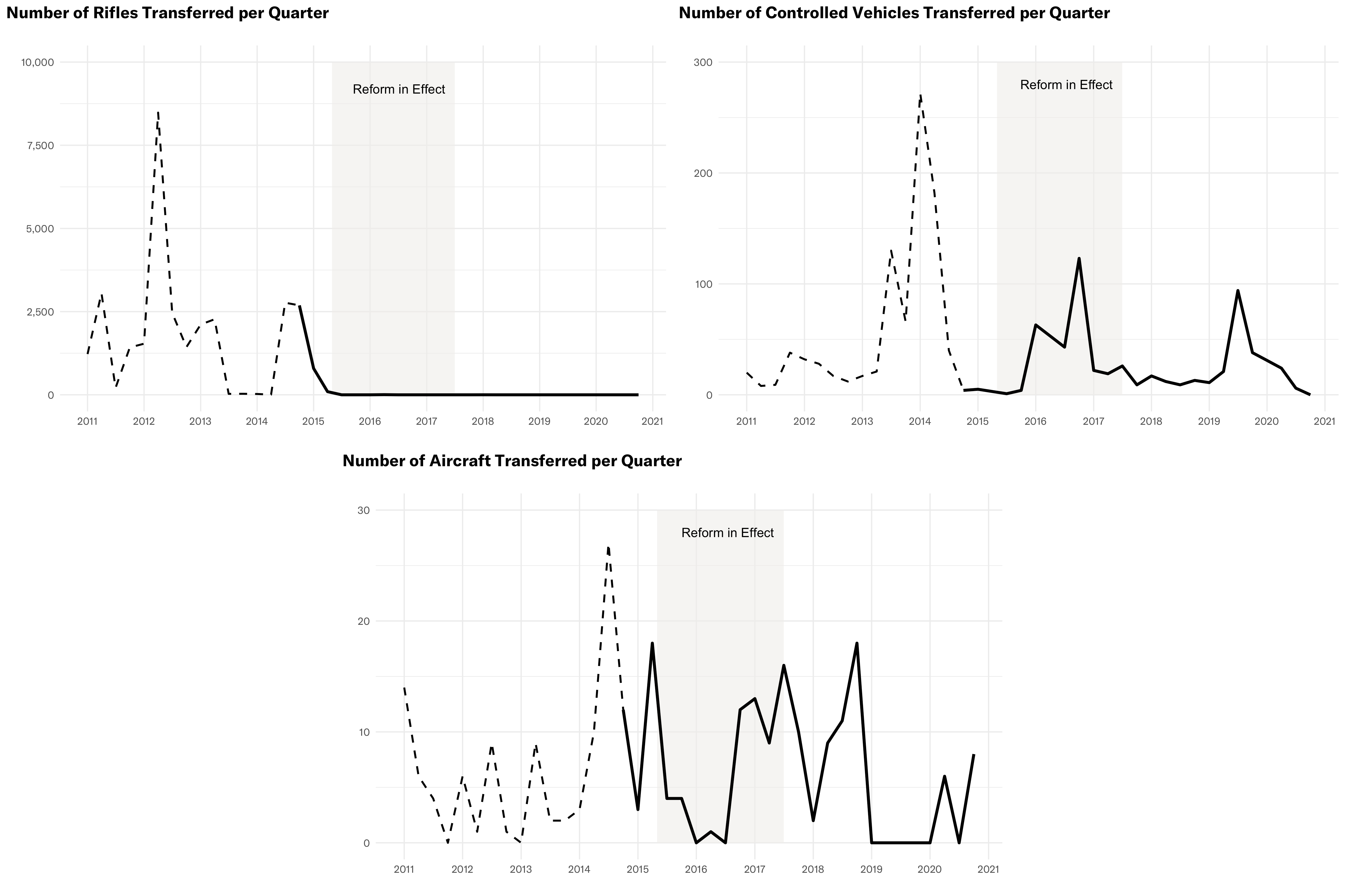

Transferred Equipment Prior, During, and After the 2015 Executive Order

If the changes implemented by the executive order constituted meaningful improvements to the safety and accountability of the program, then one might expect to see a corresponding reduction in transfers within the newly restricted categories of equipment. One would also expect that agencies not compliant with civil rights law would be removed from the program and that agencies that have no real need of militarized equipment would no longer receive it.

These charts show the number of rifles (top left), controlled vehicles (top right), and aircraft transferred through 1033 (bottom) per quarter.

The period during which E.O. 13688 was in effect is shaded. The number of military rifles sent to state and local law enforcement agencies plummeted to near zero before the reforms took effect and have remained near zero since 2017. The reforms did little to curb the dissemination of controlled vehicles and aircraft.

Yet when examining transfers over the three time periods, we do not see this expected pattern. Instead of a clear reduction, transfer patterns of restricted equipment under the Obama-era E.O. were mixed at best.

Transfers in three of the biggest categories of restricted equipment — military-grade firearms; combat, armored, and tactical vehicles, and aircraft — are displayed above. Rifle transfers dropped to negligible levels once the E.O. was enacted in 2015, but continued at near-zero since the E.O. was lifted in 2017. Militarized vehicle transfers spiked during the E.O. reforms period relative to the year before and the year after. And aircraft transfers experienced a temporary dip, but exhibited no clear pattern of significant decrease during the reforms period compared to the years before and after. Like banned equipment, the equipment restricted by the E.O. also represents a small portion of all 1033 equipment.

By the end of the E.O. 13688 period, just two months before the repeal in August 2017, state and local law enforcement agencies possessed 78,100 assault rifles and 1,400 militarized vehicles transferred through 1033. The situation after two years of “reform” is comparable to today’s landscape, more than three years after the reforms were repealed.

Today, state and local law enforcement possess more than 60,000 military grade rifles, 1,500 combat-ready trucks and tanks, 500 unmanned ground vehicles (functionally landed drones), and dozens of military aircraft, machine gun parts, bayonets, and even an inert rocket launcher. Law enforcement attached to K-12 schools, colleges, and universities have received millions of dollars of heavily militarized equipment.

Eighty institutions of higher education currently possess seven less-lethal firing devices, six mine-resistant vehicles, an armored truck, another combat vehicle, 159 shotguns and pistols, and 622 assault rifles. Nine K-12 schools’ police officers have 96 assault rifles, and one K-12 school — Spring Branch ISD — received a mine resistant vehicle in 2019.

Overall, the executive order, which provoked harsh criticism from 1033’s supporters in law enforcement and government, did very little to stop military equipment from being available for use on civilians in the course of everyday policing.

No Evidence That 1033 Makes Communities or Officers Safer

In addition to our examination of the potential impact of the Obama reforms on the actual equipment provided to law enforcement agencies, we also reviewed the existing empirical research on the stated value of providing such equipment through the 1033 program. Defenses of 1033 typically put forth the arguments that the program makes officers safer and saves taxpayer dollars.

Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions, for instance, defended the program by saying, “Studies have shown this equipment reduces crime rates, reduces the number of assaults against police officers, and reduces the number of complaints against police officers.”

The actual data, however, tell quite a different story, and the studies Sessions touted have since been debunked. In 2020, political science Professor Anna Gunderson and a team of scholars revisited the methodology and evidence behind those studies and detailed a number of fundamental methodological flaws, including that most such studies were inadequately granular to connect 1033 equipment to affected communities.

Gunderson’s team found that both studies cited by Sessions conducted their analyses entirely at the county level, comparing crime rates and assaults against officers to the aggregate amount of 1033 equipment transferred to that county. Because counties are often very large, including a number of distinct law enforcement agencies with distinct jurisdictions, an increase in 1033 equipment in one part of the county might happen to correspond with a decrease in crime in another, even though no causal effect is likely. Conducting an analysis themselves using agency-level data correctly, the team found no effect between 1033 transfers and decreased crime.

Another peer-reviewed study corroborated this finding, determining that receiving militarized vehicles had no impact on either crime rates or officer casualties. This study was particularly powerful because it took advantage of the natural experiment created in 2015 when certain types of equipment were recalled by the E.O. but others were left in circulation. Kenneth Lowande, the study’s author, found no “downside risks” of federal reforms to demilitarize police.

Another rationale of the 1033 program is that by donating no-longer-used equipment, law enforcement agencies do not need to expend their own funds and thus the program saves taxpayer money. To determine whether 1033 transfers offset these costs, we examined about 20 “most extreme” cases where we’d most expect to see a cost-saving effect of 1033 transfers — cases where police or sheriff’s departments received a large value of transfers (over $800,000) over a short, concentrated time period (one year).

Manually constructing a dataset of these law enforcement budgets from 2011-2020, we found no evidence that 1033 transfers decrease police budgets. In only one case did an influx of 1033 equipment correspond to an equivalent decrease in police spending in the following year. In all other cases, either there was no reduction in spending at all or the size of the 1033 transfers dwarfed a nominal downward adjustment.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Our examination indicates that the “around-the-edges” reforms of the Obama era were not enough to substantially curb the flow of military equipment to local law enforcement agencies. The real harms of the relatively unregulated transfer of military equipment to police forces continue to fall disproportionately on people of color.

While it is difficult to trace individual pieces of 1033 equipment to deployment by law enforcement, we can identify moments where 1033 is implicated in troubling police violence. Take the protests of June 2020, which began in response to the police murder of George Floyd, and sought to address systemic racism and violence in policing. During those protests in Austin, Texas, police critically injured a 20-year-old Black man protesting using “less-lethal” weapons. At the time, they had in their possession five “less-lethal” firing devices transferred through 1033.

Executive Order 13688 failed to curb these racist abuses. The amount of dangerous equipment in circulation remains high. Furthermore, this influx of equipment does not improve public safety. The 1033 program is beyond reform and must end for good.

Recommendations

- President Biden should place a moratorium on 1033 transfers and recall or destroy controlled equipment that has already been distributed: Until Congress can abolish 1033, President Biden must put a halt on all new transfers of military equipment to law enforcement agencies. Controlled equipment — which includes military vehicles, rifles, and other weapons of war — should be returned to the Department of Defense or destroyed by law enforcement agencies. Records and data of destruction and recall should be made publicly available on LESO’s website.

- Officially abolish 1033: When Congress revisits the National Defense Authorization Act, it should abolish the 1033 program.

- Amend Title 10 U.S. Code, Chapter 153 to create new protocols for the decommissioning of military equipment: Congress should establish new protocols for the decommissioning of military equipment that forbid the transfer of weapons of war. The distribution of all items should prioritize economic growth and community health and safety — particularly in Black, Brown and Indigenous communities that have historically been under-invested in and excluded from government grants — and environmental restoration.

- End the militarization of police: Police must be demilitarized, which requires a reduction in access to and use of militarized weapons designed for the battlefield of war, including assault rifles, grenade launchers, incendiary devices, and armored vehicles.

- End the preferential treatment enjoyed by law enforcement: Decommissioned equipment from the federal government should be distributed to the agencies and corporations that can leverage it most effectively for economic growth, community health and safety, or environmental restoration. Agencies such as schools, public health systems, and transportation departments, which have been divested from for decades, should be prioritized when disseminating federal government property and law enforcement should not be eligible for receiving this equipment.

- Divest from police and sheriff’s departments: The 1033 program is only one avenue through which the federal government funnels resources into state and local police departments across the country. State, local, and federal law enforcement agencies also receive billions of dollars in funding from the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security. All programs on the federal level that provide resources and/or funding to police departments should end immediately and the resources and funding should be redirected to alternative programs that support community safety and health.

How We Analyzed 1033

To analyze transfers before, during, and after the Obama-era reforms to the 1033 program, the ACLU used publicly available data documenting the quantity and monetary value of militarized items distributed from the federal government to local law enforcement under 1033 from 2011-2020. The Law Enforcement Supply Office (LESO), which administers the 1033 program, has published quarterly updates of 1033 equipment held by law enforcement agencies since November of 2014. Each of these quarterly updates has been collected by The Marshall Project.

In tracking these equipment transfers, LESO distinguished between “controlled” and “uncontrolled” equipment. Controlled equipment requires “demilitarization”: disposal procedures designed to ensure dangerous equipment isn’t allowed to freely circulate in the public. While LESO tracks controlled 1033 transfers for their lifetime, uncontrolled equipment is only tracked for a year after transfer, after which point it drops out of the data.

Between one inventory update to the next, new equipment transfers are made, uncontrolled equipment transferred more than a year prior drops out of the data, and controlled equipment disappears from the data when it is returned to LESO or destroyed. In addition to the controlled/uncontrolled distinction drawn by the DoD, we draw a distinction between “militarized” equipment and equipment that is not necessarily militarized. We considered militarized equipment to include: weapons, ammunition, vehicles intended for combat, aircraft, gear intended for combat conditions, and component parts or supporting equipment for any of the above. All militarized equipment is also controlled.

The data allows us to build a comprehensive picture of all new transfers since 2014, but we only have a record of pre-2014 transfers that were both “controlled” and still in circulation at the time of the first agency-level inventory update on Nov. 21, 2014. This also means that our account of transfers becomes less complete the farther back from 2014 one goes. Nevertheless, we find quantifying new quarterly transfers to be the most straightforward way to understand the effect of policy change on the 1033 program.

For much of our analyses, we report the number of items transferred rather than the total monetary value of transfers, as a small number of high-value items can bias totals significantly. At the same time, it is worth noting that equipment transfers vary wildly in terms of both item value and item unit, meaning that quantity counts are also an imperfect measure of the level of militarization created by the program. For this reason, many of our analyses report totals across specific types of comparable equipment, where possible.

Because the Trump Administration rescinded E.O. 13688 in 2017, we compared transfers within three periods of time: 1) from 2011 to the implementation of Obama’s E.O. 13688 in 2015; 2) the 2015-2017 period during which E.O. 13688 was in effect; and 3) from 2017-2020, after the Trump Administration rescinded the executive order. We choose 2011 as a starting point because it is acknowledged as a bright-line after which transfers increase dramatically, likely a result of troop withdrawals in Afghanistan and Iraq increasing military surpluses. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the data is only complete starting in 2014, and figures prior should be understood as underestimates.

Our full data cleaning, processing, and analysis methodology is available on our public github.

Acknowledgments

This article benefited greatly from contributions from Aamra S. Ahmad, Senior Policy Counsel; Sophie Beiers, Data Journalist; Kanya A. Bennett, Former Senior Legislative Counsel; Brandon Cox, Communications Strategist; Jamil Dakwar, Human Rights Program Director; Paige Fernandez, Policing Policy Advisor; Raymond Gilliar, Associate Director, Knowledge and Learning; Emily Greytak, Research Director; Aaron Horowitz, Deputy Chief Analytics Officer / Chief Data Scientist; Carson Hyde, Digital Producer; Brooke Watson Madubuonwu, Director, Legal Analytics & Quantitative Research; Rebecca McCray, Senior Editor; Cynthia W. Roseberry, Deputy Director, Policy; and Carl Takei, Senior Staff Attorney, Trone Center for Justice and Equality.