In the tragic killing of Daunte Wright, police claimed they stopped him because when they ran his plates, they found he had unpaid fines and fees. Fines and fees are part of a nationwide problem where state and local governments rely on law enforcement for revenue generation. When policymakers allow counties and states to rely on fines and fees to fund essential services, they perversely incentivize the over-criminalization and over-policing of innocuous conduct. More laws fining minor offenses create more opportunities to issue money-making tickets and, consequently, provide more excuses for police to engage in race-based surveillance under the guise of the law.

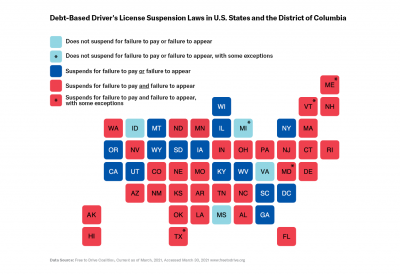

Wright’s death is just the most recent example of the devastating harm caused by employing law enforcement officers as debt collectors. Every year, there are 30 million cases related to minor infractions punishable by fines and fees — many of which give cops an excuse to make pretextual traffic stops. Our new report, “Reckless Lawmaking,” proposes a simple fix to stop over-policing and decrease income inequality: end debt-based license suspension.

In our study, we reviewed the state policy landscape and conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 16 people who had unpaid fines and suspended licenses. Each interview proved that debt-based suspensions make it nearly impossible for drivers to pay off their debts.

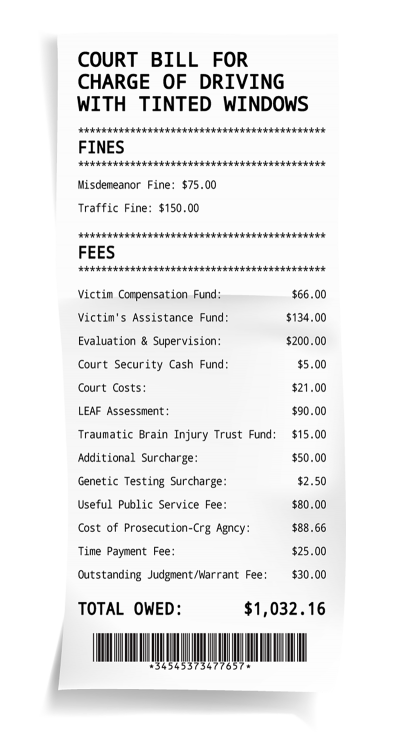

Suspensions are counterproductive to improving collection outcomes. If a driver can’t afford a parking ticket, they also can’t afford the late fee for the missed payment. Take Dario, one of our interviewees, who was pulled over by the police for “tinted windows.” When he couldn’t afford to pay the initial ticket of $225, he got slapped with an extra $807 in fees, for a grand total of $1,032. Neither the police nor the court cared that Dario couldn’t afford the charges and his license was suspended pending repayment. But because he worked 35 miles from his home, the suspension cut his income in half.

“Since I couldn’t drive to work, I lost my job,” Dario explained — a story that repeated itself across multiple interviews.

A $225 fine becomes a $1,032 debt when additional fees are added. (represents Dario’s debts).

Suspending Dario’s license for tinted windows keeps nobody safer, but the policy behind the suspension endangers many people. When policymakers rely on predatory fines and fees to fund government services, they not only impoverish drivers, they also incentivize unnecessary encounters with the criminal legal system and waste city resources. Our interviewees faced required court appearances, compounding criminal charges, and even jail time for failure to pay. For example, our interviewee Jessica from Florida had her license suspended when she could no longer afford her car insurance premium. When she missed a court date, she was arrested for failure to appear.

Police enforcement of fines and fees also increases contact between drivers and police. Because cops can identify unpaid fines and fees with license plate readers, police enforcement of missed payments justifies pretextual police stops. At best, these stops result in additional fines for drivers struggling to pay original fines. At worst, these encounters escalate to violence or death. Just last week, an unpaid fine gave former officer Kim Potter a pretext to stop Daunte Wright. The stop ended with Potter fatally shooting Wright.

Even when pretextual policing doesn’t result in death or police brutality, it still has devastating mental and emotional health consequences for impacted individuals. “When I got to court, I almost had a nervous breakdown,” relayed our respondent Rosie from Colorado. “I thought, ‘This is just one ticket.’ Then I saw I was facing actual criminal charges. I couldn’t breathe.” Another respondent, Katy, shared, “I had my small child with me at the time. It was very traumatic. The cop was very aggressive and threatening.”

Our report gives policymakers multiple recommendations:

- Driver’s license suspension should not be used as a penalty for failure to pay or failure to appear, regardless of the underlying offense: States should make it easier, not more difficult, for people to comply with payment by instituting reasonable payment plans, retroactively reinstating suspended licenses, and waiving reinstatement fees.

- All fees should be eliminated: The government should end fiduciary reliance on fines and remove perverse incentives for law enforcement to criminalize drivers based on income level.

- Existing prescribed dollar amounts for fines should be replaced with income-based measurements: For example, payments could be based on one day’s pay or 1 percent of monthly income.

- Lawmakers and court administrators should provide robust, timely notice of payment and court obligations: Information about payment and license reinstatement should be easily accessible.

- States should collect demographic data for debt-based driver’s license suspensions: Given the racial and economic disparities throughout the criminal legal system, states should routinely collect demographic data in all cases where fines and fees are imposed and collected.

- States should regularly collect relevant data needed to assess the fiscal impact of fine and fee related license suspensions: Fiscal notes related to license suspensions should consider the scope of the impact, the cost of enforcement, and collateral costs to drivers from job loss, eviction, and economic mobility.

Our legal system should benefit the people it serves. Taking away driver’s licenses from people struggling to pay their debts is bad public policy, plain and simple. We need policies that reflect the economic reality of Americans surviving a pandemic, recession, and gilded-era wealth inequality. It’s common sense: Debt-based license suspensions are bad public policy.

Michelle Borbon, Communications Assistant, ACLU National